Part of the Van der Hammen reserve, with developments visible in the background

Proposed developments for Bogotá’s humedales have sparked fierce debate about the need to preserve the capital’s wetlands against the need for housing and infrastructure – Diana Mejía takes a look at what’s at stake

Like many cities, Bogotá has historically had a deep-seated relationship with water, dating back to the Muisca peoples who inhabited the savannah. Early maps from the first settlers show carefully laid out water networks including the páramos – the uniquely Andean moorlands – which supplied the city with its fresh water. The rivers flowing from these páramos fed the ample humedales found in the valley, and are estimated to have covered over 50,000 hectares of the Bogotá savannah at the turn of the 19th century.

Humedales are ecosystems with shallow, permanent or seasonal bodies of water where plants with wet roots flourish. The importance of wetlands is hard to understate; they protect against flooding by acting as sponges during the rainy seasons, help fight erosion, replenish the water cycle and act as sanctuaries for wildlife.

The rapid expansion of the city over the last century has come at the expense of wetland and water networks, with infrastructure and urbanisation projects swallowing them up at every step. In fact, an estimated 60% of the city has been built over wetlands; while several thousand hectares of humedales existed in the 1800s, only 500 hectares remain today. Many developers have used surrounding wetlands to deposit construction debris, thus draining the water and paving the way for future development.

Restoration and conservation initiatives have flourished in recent years, with commitment from the city to help in the preservation work. Currently, Bogotá has 15 humedales throughout the city, while the foundation Humedales Bogota (Bogota Wetlands) lists an additional 13 wetlands which are not yet recognised.

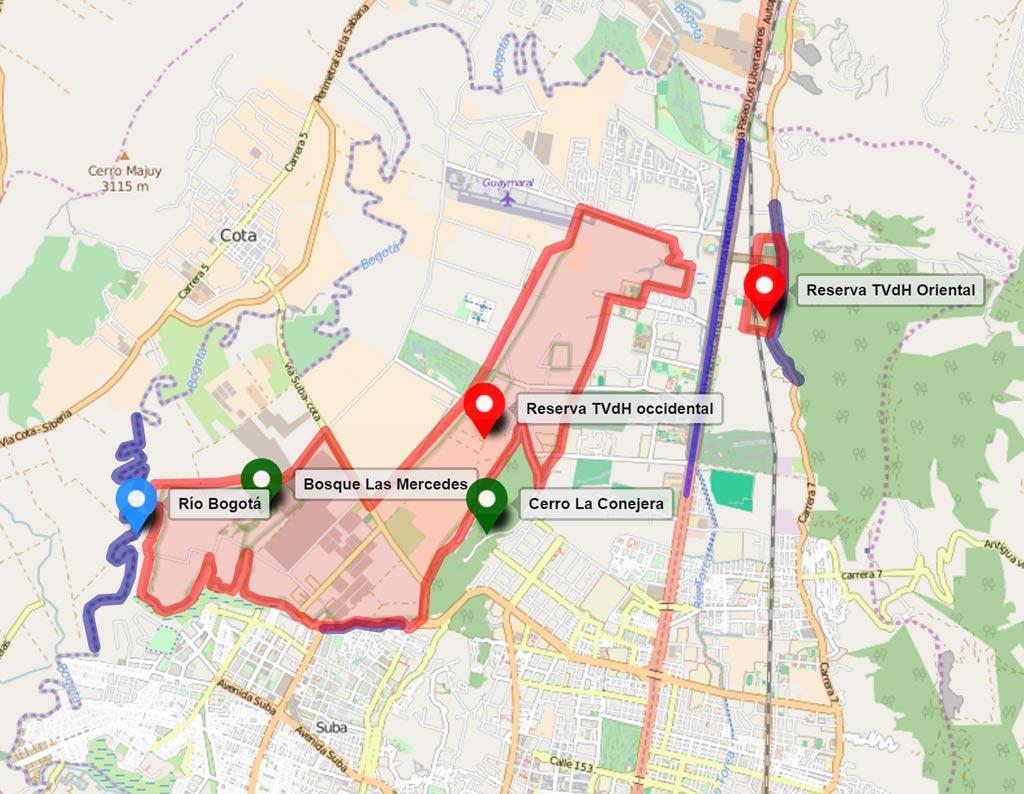

Map of the Suba area of Bogotá, outlining the area covered by the Van der Hammen reserve in red. Green signifies wooded areas and blue the Río Bogotá. Photo: Wikipedia

The Van der Hammen Forest Reserve

At the northwestern edge of the city, in the Suba locality, lies the Van der Hammen Forest Reserve, a strategically located undeveloped space which connects the Conejera and Torca-Guaymaral wetlands, the Conejera hill and the Rio Bogotá.

Environmentalists have been trying to protect the 1,350 hectare expanse – ten times the size of Simon Bolivar park – since 1999. While the reserve is not a wetland, it hosts hundreds of unique plants, six species of small mammal, 181 bird species and 23 species of butterflies as well as some plants in danger of extinction.

After numerous studies carried out by some of the leading environmentalists in the country, the Van der Hammen reserve was recognised by the Cundinamarca Regional Autonomous Corporation (CAR) in 2011 as an “East-West connecting axis of the main ecological matrix of the savannah which connects the mountainous systems that surround it with the floodplain of the Bogotá river and its wetland network”. In 2014 a restoration management plan was agreed by the CAR, whereby the area would be converted, over the next 20 years, into one of the largest urban connectivity ecosystems in Latin America.

However, this land does not belong to the city, but to private individuals whose homes and businesses (mostly greenhouse farms) are located in the reserve. Construction projects have been frozen since 2000 when the reserve was identified as an area of interest, but the existing structures have remained in place. Buying these lands for the development of the forest reserve would be a costly investment, with estimates as high as three billion pesos.

Mayor Peñalosa has made clear (since his first administration in 1999) that he does not share the views of environmentalists or the previous administration regarding the importance of restoring this territory. In fact, Peñalosa himself has described the reserve as a “mostly deforested [area], with pastures, greenhouses and fields in private hands”.

The city argues that only 7.8% of the total area is a conservation ecosystem, while the remaining land is taken up by sports areas, schools, industry, debris, houses, shops and livestock fields.

Developments such as this have already spread into Bogotá’s natural wetlands.

Urban development and the government’s green promise

In early February, the mayor’s office announced details of its Ciudad Paz project, which would take 15,000 hectares of the city outskirts and allot them for development in order to guarantee housing for a projected three to four million people over the next 30 years.

The project is divided into four sub-categories: Ciudad Norte, Ciudad Rio, Ciudad Mosquera and Ciudad Bosa-Soacha. The northern development would urbanise some 5,000 hectares, including a significant portion of the Van der Hammen conservation zone.

In addition, the administration would construct part of the Avenida Longitudinal de Occidente, a proposed highway which would allow an alternative entry-exit point in the northern part of the city, as well as an expansion of Avenida Boyacá and Avenida Cali, in the reserve.

In order to urbanise the area and build the proposed highways, over 90% of the Van der Hammen Reserve would be developed, leaving only 7.8% under continued protection. This would include the wetlands which cover 0.64% of its area.

Some of the biggest beneficiaries of the project would be the current landowners, whose land value would increase by the zoning change and could then be sold to developers, not to mention the potential developers and construction companies hired to build the mega-infrastructure projects.

The mayor’s office has offered assurances that the urbanisation plan would be sustainable and maintains that the ecosystem would be connected through linear parks that would maintain migration routes from the Río Bogotá to the mountains.

The Bogotano Tingua, one of the species under threat of extinction with the disappearance of the humedales. Photo: Wikipedia

Concern from environmental groups

In response to the proposed green corridors, environmentalist and former environment minister Julio Carrizosa explains that the ecological structure of the Van der Hammen reserve doesn’t depend only on trees or vegetation, but on the interaction between rainwater and underwater springs. The draining and urbanisation of existing wetlands could cause these water sources to completely dry up.

Carrizosa sees the urbanisation of the Van der Hammen as “a sign to municipalities that they don’t have to keep protecting agricultural land and that they can urbanise the whole savannah without protecting land”.

In addition, environmentalists argue that the urban sprawl would completely destroy green belts between urban centres both within Bogotá and in surrounding areas. They foresee the eventual adjoining of Chía and other satellite towns without any sustainable agricultural land in between.

However, in an interview with Semana magazine, planning secretary Andrés Ortiz maintained that “it would be worse to have disconnected municipalities 20 or 30km from the city without the possibility of public transport”.

The road ahead

The administration’s proposal is far from a done deal. In order to urbanise the Van der Hammen reserve, the city must receive approval from the CAR as well as the Ministry of the Environment. Ortiz is confident that “the formal initiative contains solid environmental studies to suggest a land-use change for this sector”.

Whatever the future of the proposed urbanisation plan, it has certainly opened a fierce debate about the preservation of Bogotá’s surrounding green spaces and the growth of the city.

Whether the city densifies or continues to expand, both current and future administrations will have to come to a consensus on how best to deal with the millions of new people expected to call Bogotá home within the next few decades.

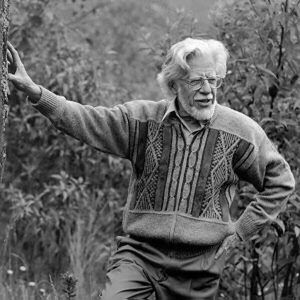

Thomas Van der Hammen. Who is Van der Hammen?Thomas Van der Hammen was a Dutch naturalist who arrived in Colombia in 1951, aged 27, and began a love affair with the country – and its nature – that would last his whole life. The avid geologist, botanist and archaeologist collected and documented the country’s soil, flora and vegetation, writing over 400 academic publications. He championed the creation of the reserve which bears his name: a group of forests, fields and other lands that have been protected since 2000, and connects the Río Bogotá to the eastern hills. Van der Hammen passed away in 2010, aged 85, and is remembered today as one of the leading environmental researchers of the Bogotá savannah. |

By Diana Mejía