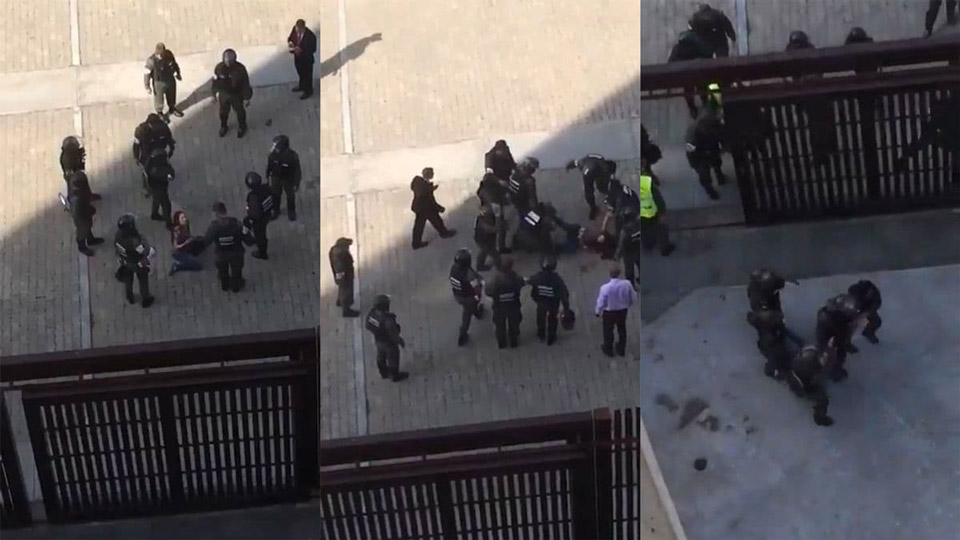

Venezuelan National Guard surrounding, beating, then dragging away Caracol journalist Ely Angélica González.

Colombia ventures criticism and casts careful glances at the deepening crisis across its border with Venezuela.

The already-strained relations between Colombia and Venezuela have deteriorated further in recent weeks with a string of incidents that have put pressure on the two countries.

Venezuela is in the midst of an economic crisis, with hyperinflation rampant and shortages of basic goods. President Nicolás Maduro is under pressure as street protests calling for his resignation are gaining momentum.

In late March, Venezuelan military forces made incursions into Colombian territory, near the border with the department of Arauca. The Colombian military was deployed, though Venezuelan authorities later claimed the incident was a mistake caused by the changing flow of the Arauca River.

Then, on March 29, the Venezuelan Supreme Court assumed control of functions normally reserved for the National Assembly, which is controlled by opposition factions hostile to Maduro. This lead to a dissolution of parliament, generating an outcry in Venezuela as well as condemnation from other countries in the region.

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay and Paraguay, all members of the Association of South American Countries (UNASUR), signed a letter expressing concern over the actions of the Supreme Court. President Santos, who had previously avoided directly criticising his neighbouring head of state, commented that “[these actions] destroy the pillar of any democracy, which is popular representation.”

Abruptly, on April 1, the Supreme Court changed tack and reversed the decision. The reasons are unclear, although it seems likely that Maduro realised this may have been a step too far, both domestically and internationally.

A further complication involved an incident with Caracol journalist Ely Angélica González, who was covering the events in Caracas. Videos appear to show Gonzalez being detained and beaten by members of the National Guard. Although the journalist in question is Venezuelan, Colombia is treating the affair seriously. Foreign Minister María Ángela Holguín expressed “concern and rejection at this attack on the free exercise of freedom of expression.” Ambassador Ricardo Lozano was also recalled from Caracas for advisory talks in Bogotá.

Finally, the state of flux on the Colombo-Venezuelan border continues to generate a sense of instability and unpredictability. Severe economic turmoil has many Venezuelans, as well as Colombians residing there, looking beyond the border for opportunities. The numbers of migrants coming into the country are hard to pin down, as those with dual nationality crossing the border are difficult to keep track of. However, among those who entered Colombia with Venezuelan passports between 2013 and 2016, Migración Colombia estimates that over 300,000 have stayed in the country, both legally and illegally.

At this stage it’s unclear what will happen next. As Santos commented, Colombia will act with prudence as “we are the country with the most to lose or gain from the Venezuelan crisis.”