The new look of Calle 12C with Carrera 1A. The graffiti that had been here for years has been painted over. Photo: IDPC

A government initiative to protect historic buildings has proven controversial. The city faces challenges as it tries to balance the popularity of graffiti against the need to renovate La Candelaria.

Wander up the narrow streets of La Candelaria that lead to the Chorro de Quevedo, the plaza packed with chicha-guzzling punters and street performers, and you might notice that some of the buildings have a new white-washed appearance. The crooked walls of the narrow cobbled Carrera 2 – fittingly named Calle del Embudo (funnel street) – which used to be filled with graffiti have recently received a new lick of paint. The buildings have been restored to their original white, the colour they would have been when they were built in the 16th century.

It’s part of an Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultural (IDPC) initiative to preserve the city’s heritage sites. Unfortunately, the plan has sparked rumblings of concern among some urban artists and members of the public, who fear that this is part of a wider conspiracy to rid the city of graffiti. Some see the paintings as an urban art form, while others consider it a form of vandalism.

Graffiti’s growing recognition as an art-form as opposed to an act of rebellion creates a headache for city administrators around the world. For example, painting over Banksy’s now priceless works is a source of outrage, whereas few would object to cleaning up a generic “Dave woz ‘ere” that had been scratched into a wall.

In Bogotá, urban art has come to play an emblematic role, putting the city on the map for art-inspired youth and tourists alike. Many areas of concrete jungle, like the Avenida 26 or NQS, have become majestic outdoor galleries where artists can express themselves freely.

The Bogotá Graffiti Tour, created in 2011, is recommended as one of the best tourist draws in the capital. Running twice daily, it promotes local artists and reveals the inspiration behind certain works. “There are tons of Colombian artists that are travelling around the world and tons of international artists that are coming here to get an opportunity to paint,” says tour guide Jay. “Bogotá’s graffiti culture has been covered by many media outlets nationally and abroad, making [it] both a tourist attraction and an icon of the city.”

Reasons to erase

The popularity of graffiti is one reason why La Candelaria’s new makeover is a cause for concern. Some murals have already been painted over and others have been earmarked for the whitewash treatment. Policy-wise, this is where the IDPC renovation drive meets the council’s Decreto 75, an act created by former mayor Gustavo Petro that aims to promote the responsible and legal practice of graffiti. It designates clear no-go areas, including the TransMilenio, trees and public footpaths, as well as areas of cultural interest. Urban art is not authorised on “cultural assets of the city, of national and regional interest, as well as the city’s monuments and sculptures.” That includes the historic buildings and statues of La Candelaria which were designated as a cultural heritage site in 1963.

Graffiti in Bogotá is slowly losing ground against the administration who want preserve historic buildings.

According to IDCP spokesman Diego Parra, their ambition is to “incentivise and motivate a culture of preservation in areas of historic heritage.” In order to achieve this by their 2020 deadline, the IDCP has created innovative schemes like Adopta un monumento, where a person or organisation can adopt a monument, becoming responsible for its renovation and upkeep. This is no easy feat and can cost a pretty penny. The Obelisco de Los Mártires, which sat invisible and vandalised in the Bronx’s Plaza de los Mártires for many years, was adopted by the Batallón de Reclutamiento and cost COP$77 million to renovate.

The actual restoration of such monuments can be highly complex, but at least there are no questions about who is actually responsible. It’s a different matter when it comes to the façades of privately-owned walls, especially those that boast internationally-renowned street art. Many property owners originally gave permission to the graffiti artist and in some cases paid them. Somewhat surprisingly, Parra says that there are only a few cases where the property owner has said no to renovation.

Related: Los Puentes: colouring a community

“First we spoke to the community,” says Parra. “We did this by going door-to-door, getting the owners’ authorisation. In many cases they said they were tired of the mural and that it has had its time.” In keeping with the mission to develop a sense of responsibility, owners are invited to contribute to the work with materials or labour.

When it comes to graffiti, the IDPC’s stance is clear: the preservation of historic buildings takes precedence over the protection of urban art. Once the owner has agreed to plaster and paint the wall, they will have to ask for permission before making any alterations – including painting another mural.

Consequences of renovation

While losing a piece of celebrated art is saddening, for the IDPC it is an unavoidable consequence of their renovation plans for around 2,500 façades of listed buildings. “We are completely aware that urban art in the historic centre, and more specifically in La Concordia neighbourhood [Chorro de Quevedo] has national and international recognition, and we are in favour of this artistic expression, but always when it follows the regulations and laws.”

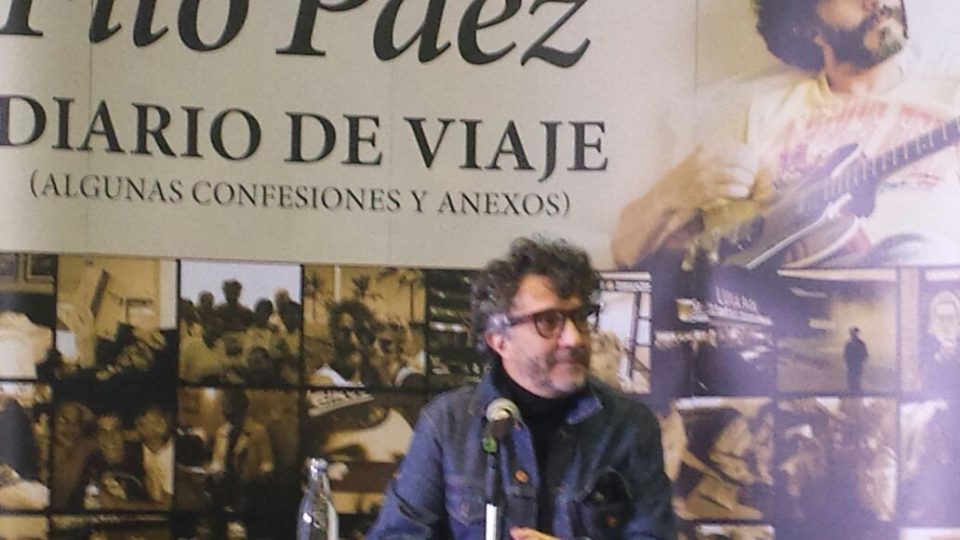

- Calle 12C with Carrera 1A before the cleaning operation. Photos: IDPC

- Calle 12C with Carrera 1A after the cleaning took place.

- Calle 12B Bis with Carrera 1 before the cleaning operation.

- Calle 12B Bis with Carrera 1 after the cleaning took place.

- Carrera 3 with Calle 12F before it was cleaned.

- Carrera 3 with Calle 12F after it was cleaned.

But many members of the graffiti community think the council has just created a new problem for itself. For example, it is unusual for people to ‘tag’ murals painted by established artists, whereas the blank canvas of the open walls is an open invitation.

“I don’t believe the city will do a good job at keeping the graffiti off of the walls,” explains Jay. “Some of those walls that have been painted over have already been tagged, some have been painted for a second time and have already been tagged. In reality that’s what’s going to continue happening. The taggers will continue to tag empty one-colour walls, those are perfect spots for them and it’s going to cost the city a lot of money to continue to paint over walls.”

The issue with the Alcaldía’s regulations is that graffiti doesn’t exactly go hand-in-hand with obeying the law. Artists often gain respect for painting in the most unreachable spots, and there’s a strong belief that every wall is a potential blank canvas. Grafiteros are naturally anti-establishment, so agreeing to designated spaces goes against their rebellious spirit, and perhaps even offers an incentive to paint where they shouldn’t.

Working together

The challenges of bringing the establishment and the anti-establishment together become even clearer as Jay explains, “The city also wants to change graffiti in a way, they want to regulate it and make sure these kids don’t go out and do illegal stuff, and that will never happen. They want to make sure to take credit for ‘everything they are doing’ for graffiti. So that starts to put a big part of the community against them.”

However, others see examples of collaboration with authorities – such as the work being done here between the IDCP, the city council and a local board of urban artists – as the beginnings of a new relationship based on mutual respect.

Yurika, an internationally recognised graffiti artist, explains: “When I was 18, I didn’t care. I didn’t understand what architecture was, now I understand and appreciate the other artist.” Now 33 and working with the IDCP, his work can be found throughout Colombia. “Obviously you feel sad when a piece gets covered, especially when you’ve bought the paints, but graffiti is ephemeral and I have photos.” He does admit that his favourite pieces are those that appear overnight, dangled from ridiculous heights.

Jay voices a less conciliatory sentiment. “The council are not all anti-graffiti,” he says. “I know a lot of good people that work for the city that really go out of their way to make all these projects work, the problem are the higher-ups, the bosses, the people that actually make the decisions and it comes down to this, rich people don’t like graffiti.”

Related: Graffiti’s new stroke – from the street to the gallery

He continues, “As long as they are part of the council you will always have a backlash and every time some really illegal piece goes up like on August 16, when a whole TransMilenio was painted – three whole cars – that’s their chance to say, ‘see we told you, they’re all criminals.’”

Natalia Bonilla, the coordinator of the local board of graffiti artists on behalf of the secretary of culture, entertainment and sport (IDARTES), believes that the mistrust felt by some members of the artistic community is due to misunderstanding the IDPC and the council’s intentions. “We need to understand it’s not about painting for the sake of it, it’s because of the decree and rules you shouldn’t paint there,” says Bonilla.

Council involvement

“What people see is something negative, but actually it’s something completely opposite.” Bonilla points out, referring to Enrique Peñalosa’s considerable investment into urban art projects. On August 31, the day of urban art, IDARTES announced an investment of COP$1,500 million and a competition for national and international artists that will close on September 22. “If you look at the figures of who has invested most in urban art, last year in only six months, we doubled what had been invested by the previous mayor,” says Bonilla. “It’s investing in responsible urban art.” This sizable investment challenges the public opinion that former mayor Petro was pro-graffiti, whereas Peñalosa is trying to rid the city of it.

On November 22 last year, international artists such as Barcelona’s Pez and UK collective The London Police joined local artists, supported by the city council, to paint 32 murals in the industrial area of Puente Aranda, turning the bleak industrial area into a centre of urban art. “It went really well, and if you go there people are doing things, people are visiting the area where before nothing happened,” says Bonilla. “Through urban art you can renovate spaces and restore public areas.”

Bogotá mayor Peñalosa is a strong force behind getting rid of graffiti

This all sounds extremely positive. However, the state funding of murals and the designation of “graffiti friendly areas” does raise the question of censorship. Will the state really want to fund anti-establishment pieces of art? According to Bonilla, this isn’t a problem. “We never tell an artist what they should or shouldn’t paint,” she clarifies. “What we hear from artists and people coming from abroad is that Bogotá is very tolerant with this.” With this in mind though, artists in state-run competitions are given themes to work with, like Las Sierras, or gender. However, the tour guides on the Bogotá Graffiti Tour do mention that the council is not fond of overly political murals in the historic centre, preferring to keep them out of the tourist hot-spot.

Related: Sign up for the Bogotá Graffiti tour

It does appear that the IDPC’s commitment to restoring historic façades is not a pretext to wage war against urban art, and neither is the council’s sizable investment in responsible practices a conspiracy to silence free expression. However, Jay does tell me that some artists have complained that the materials provided are not up to par, and that the mayor’s slogan ‘Bogotá Mejor Para Todos’ is plastered on it as soon as the project is finished.

It is understandable that many artists remain suspicious towards the authorities. For example, in 2011, a police patrol murdered Diego Felipe Becerra, a young graffiti artist then, two years later, escorted Justin Bieber to leave his own mark on that very wall.

Such events may have nothing to do with the work of the IDPC or IDARTES, but they have fostered distrust. Both public institutions repeatedly stress their commitment to urban art. “We don’t want graffiti to disappear from the historic centre,” says Parra. “Historical patrimony is not the district’s, it’s not Peñalosa’s, it’s everyone’s and we have to look after it.”

Phoebe Hopson