We joined the protesters on the streets of Bogotá on Thursday to hear about their hopes and concerns.

The November 21 protests will remain in the memories of Colombians for years – even decades – to come. Hundreds of thousands of people filled the streets of Bogotá, and towns and cities across the nation, holding signs and yelling chants of discontent in what as one of the largest Colombian protests in recent years.

The people we joined in the Bogotá marches were protesting over various long-standing grievances including labour reform, education, violence against indigenous communities and the implementation of the peace agreement. Many also shared their anger about the murder of the eight children in Caquetá.

A number called for the departure of President Ivan Duque, with numerous protesters touting signs with pig imagery and slogans playing on his now infamous interview in which he responded “¿De qué me hablas, viejo?” to a journalist in reference to a question about the murdered children.

Throughout the day the sound of explosions of gas canisters punctuated the chants calling for Duque’s resignation. The heavy rain did not deter the marchers who were of all ages and backgrounds.

Several protest routes culminated in Plaza de Bolívar, where thousands of people stood in the pouring rain, huddled under umbrellas as leaders on a central stage roused the crowds with complaints and calls to action.

Colombia protests largely peaceful

While protests were largely peaceful, images of government violence circulated on social media, with one photo from El Tiempo showing police kicking a protestor. In the capital, there were violent clashes between the ESMAD riot police and students at locations near the Universidad Nacional, as well as the road towards the airport. Tensions also ran high with clashes in suba and the roundabout on calle 53 with carrera 50.

Valentina Laguado, a 21-year old Universidad Cundinamarca student said a police officer hit her and sprayed tear gas in an area where children were present. She said her and her friends were dissatisfied with the country’s healthcare, especially the long waiting times for appointments, and with government proposals to lower the minimum wage.

“We want to create a revolution in Colombia. And for all of Colombia to come together. Because here there is a lack of unity and that’s why they are always attacking young people and saying they are vandals,” said her friend, 20-year old Universidad de Cundinamarca student Jessica Díaz. “But they don’t understand this is a battle for everyone. For their pensions, work for their kids, everything. It’s for the people.”

These sentiments were echoed by journalist Rodolfo Alarcón: “We’re here first for the bombing of the children in Caquetá, second for labour reform, third because I’ve never had a decent contract in this country. It’s always been [temporary] contracts for the provision of services.”

“Also because I’m against all of the armed violence, for the deaths of the indigenous people in Cauca and that [the government] isn’t saying anything. For the reaction, the indolence of this government that I didn’t choose,” he said, adding his frustration with social inequality and environmental degradation.

Lida Rivera, an archive manager said she was marching for better healthcare, for free education, for an end to corruption, unemployment and for the ousting of President Duque. “My hopes are that the quality of life improves,” she said.

Others also cited dissatisfaction with how the government was handling the implementation of the peace agreement with the FARC, and a fear that the country would revert to civil war.

“Since my childhood I have always lived in war. And that has changed, but now it feels like it’s coming back,” said Julian Amaya, the owner of a software development company. “And I don’t want the new generation to live what I lived when I was younger.”

Government reaction

Many protestors also expressed anger and frustration with the government reaction to the protests, and expressed suspicion that they would send infiltrators to cause chaos and discredit the march.

Read more on Colombia’s national strike:

November 21 in photos

“Police has been respectful to protocols” – Peñalosa

All about Colombia’s national strike

“I feel like they’ve been trying to make this just a political march and it’s not. People are really unhappy,” said Amaya. “It’s not like I’m from this party or something. We are not happy with the way the government is working.”

Human rights lawyers Laura Baron-Mendoza and Estefania Vargas wanted an end to armed violence, implementation of the peace accords, and lamented the deaths of social leaders, ex-combatants and falsos positivos.

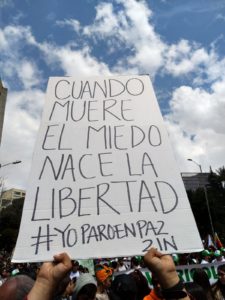

We are not afraid

“They are afraid of us because we’re not afraid,” said Baron-Mendoza. “We’re not terrorists, we’re not guerrillas who are going out to march. We are people with hope, with aspirations for a different country. And we are tired, tired of being stigmatised just for thinking differently.”

Protests continued into the night, with crowds coming down Séptima as late as 8pm and increased reports of violence after night fell. As many demonstrators returned to their homes, a “cacerolazo” or cacophony of residents banging pots and pans out of their windows filled the streets in some areas for several hours. Whole families, some in their pyjamas took part in what appeared to be an organic demonstration. Pot-bangers in the north of the city said they would go to the President’s house.

The paro nacional included protests all over the country, including in Medellín, Cali, Cartagena, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga and Santa Marta. Cali was the city that saw the most difficulties, as several policemen were injured in confrontations with the protestors and we received reports of looting in parts of the city. This is why mayor Maurice Armitage imposed a 7pm curfew, according to the Ministry of the Interior.

It remains to be seen what Friday will bring. Bogotá mayor Peñalosa has already announced that the TransMilenio will not be operational, and today’s protesters were talking about continuing to march.