Colombia is off to the polls in a little under a month, but what’s at stake and what could happen? And why can’t you have a drink while watching results roll in?

Every Colombian over the age of majority (18) and with a correctly registered cédula ciudandanía can vote. In return, each voter gets a half day off work. Non-citizens are not eligible to vote in national elections, but holders of resident visas will be able to vote in next year’s local elections.

The polls are open from 8am until 4pm and counting is usually very fast with the first results coming in just an hour or so later. Due to the PR system (see below), final results come through in the week.

Land and fluvial borders will be closed for Colombian nationals on the day of the election, although foreigners can cross. From the Saturday afternoon before voting until the Monday morning, ley seca will apply, meaning no alcohol sales in bars, restaurants or shops. That applies for everyone, so no representation or boozing.

Oversight is carried out by the CNE (Consejo Nacional Electoral). In order to do this over the vast territory and number of stations, over 800,000 citizens are selected to be vote-counters. This is similar to jury duty in other countries and is compensated with a day off as well as a compulsory day of training a couple of weeks beforehand.

As the electorate is growing, there are now some 13,000 voting sites across the country, most with multiple voting tables. Colombians have to vote where their cédula is registered, so don’t be surprised to see some people trekking to other cities if they forgot to update their registration.

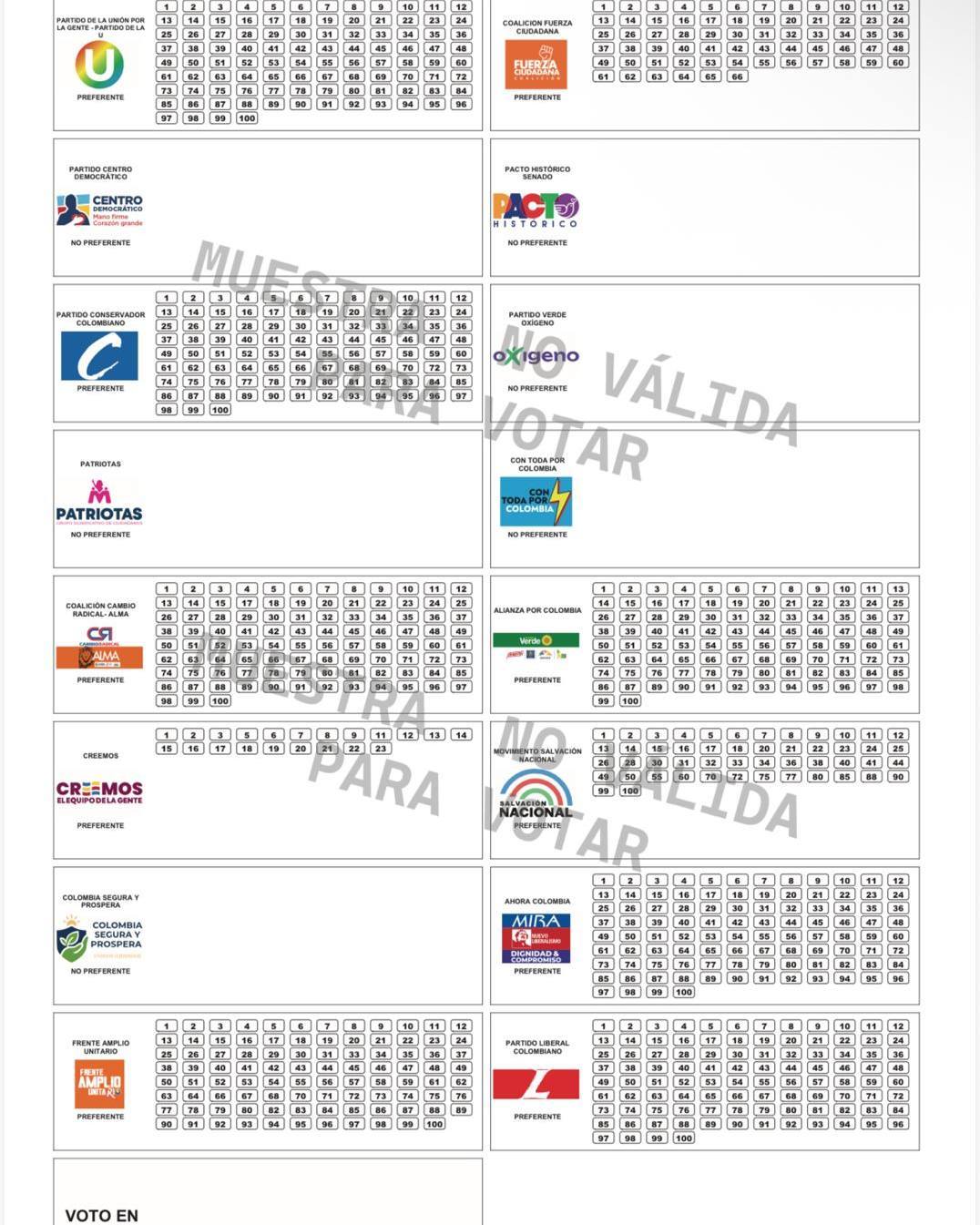

Some parties run a closed list system, meaning you simply vote for them, whereas others have open lists, meaning you vote for the party and can also vote for your preferred candidate within the party. For closed lists, the party will decide who enters congress, with an open list it will be done in order of preference.

A smidgen under 50% turnout is common for house elections, with higher figures expected for the presidential elections later this year. The Colombian parliament is a bicameral system with the Senate acting as the upper and more powerful house and the Cámara the lower house.

Most parties do not really have well-defined manifestos as such, although better-funded candidates will give a range of positions on matters. In general, there will simply be slogans and general aims that give voters an idea of where their candidates stand.

Who’s up for election?

With a PR system in place there are a plethora of parties to peruse. The country was dominated for decades by the Conservadores and Liberales and both remain strong across the country. In recent years they’ve been joined by the Centro Democrático as the third force. Expect all three to do well.

Mid-level parties include the likes of the right-wing Cambio Radical, particularly strong on the Caribbean, centrist (and not ecologically centred) Alianza Verde and ex-president Santos’ centrist partido de la U. The last election saw the leftist Colombia Humana rocket up to join these blocs.

Then there are the smaller parties, often operating essentially as almost one-man-bands. These usually have an enormous amount of support in a particular area or for a certain candidate but fail to translate this to a wider audience. It’s common to see them banding together, as with the governing coalition Pacto Histórico.

Finally, there are guaranteed seats in both the Senate and Cámara for certain groups and people. This year sees the Comunes party no longer receiving an automatic five seats in both houses that they had in the last two votes as part of the peace process.

If you are a fan of PR, this system allows a diverse number of voices to be heard and limits the power of government, especially when there is opposition to their plans. For those more cynically-minded, it is a way to make sure that little gets done and few significant bills are passed.

There’s also the curious option of voto en blanco. Different from a spoiled vote, which is simply disregarded, this is an active protest. If it ranks highest in any race, then a rerun of the election must take place within a month with entirely new candidates and/or party lists.

Colombian Senate Elections 2026

The Senate now has 103 seats (known as curules) and is the upper house in the bicameral system. Of those, a straight 100 are chosen by the electorate as a whole, while Indigenous communities select a further two and the runner-up in the presidential election will receive the final seat.

The Senate currently boasts a whopping 17 parties, but only six of those have double figure representation with the Conservadores’ 15 being the biggest single group. 26 parties are running 1,000 candidates between them this time. Voting is done on a national basis and tallied up across the territory, meaning this takes a little while to work out.

While there is a diverse group of parties, they hang together in loose blocs roughly delineated as government, opposition and neutral. With the government only controlling 34 curules and the opposition 24, the neutrals are incredibly important for horse-trading.

This will be a huge litmus test for the ruling leftist bloc. They will lose their guaranteed Comunes seats, so any further losses will be highly problematic. On the other hand, gaining curules would be a huge shot in the arm in terms of public support, hence why they are campaigning in places like Huila, outside of their traditional strongholds.

The most likely outcome is that there will be little change in the makeup of the Senate, with neither the government nor opposition likely to take outright control or make large gains. Whichever of those two groups increases their representation will quickly turn it into a sign that they are on the right track and use that as support for their presidential campaign.

Cámara de Representantes election Colombia 2026

The lower chamber, too, is also up for election. It is significantly larger, with 188 seats and 23 parties. The government is also in a minority here and relies on support from independents to get things done. There are over 2,000 candidates representing nearly 500 parties, or listas of similar candidates.

The key difference in voting here is that it is largely territorial, with 161 seats divided between the departments and Bogotá, DC. The latter returns the most seats, with 18, closely followed by Antioquia with one fewer. Colombians living abroad and voting in embassies get one between them

However, these are not equal, as departments receive at least two seats, meaning Vaupés gets one representative for every 20,000 or so people, while the national average is more like 300,000. Changes in population have led to odd situations like Caldas returning more representantes (5) than Cauca (four) despite only having ⅔ of its population.

Then there are the special seats. Again, the Comunes party will lose their five extra seats in this term and it is also the last election to feature the 16 seats reserved for conflict victims. Colombians of Afro descent get two seats, while Indigenous Colombians and raizales from San Andres and Providencia have one apiece and the VP runner-up rounds it out.

Consultas for the presidential election

Just in case you thought there was enough on the plate, there are further considerations at stake. To avoid spreading the vote, various presidential candidates with similar positions group together for a preliminary vote. The losers in each consulta will drop out on March 9th. This year there are three on the voting card.

The biggest of these with 9 names is the Gran Consulta Por Colombia, which stretches the credibility of political similarity. It’s nominally centrist but features prominent rightists Vicky Dávila and Paloma Valencia alongside traditional centre voices such as Enrique Peñalosa and Juan David Oviedo. The latter is also the Centro Democrático candidate.

The leftist consulta is under intense scrutiny as candidate Iván Cepeda, currently leading the polls, was blocked from taking part. That led to further withdrawals and angry denunciations from Cépeda and sitting president Gustavo Petro. Roy Barreras is now the favourite to win this five person race.

Then there’s a centrist competition between former Bogotá mayor Claudia López and little-known candidate Leonardo Huerta. López is the clear favourite here after perennial runner Sergio Fajardo chose to go directly to the first round of presidential voting.

At the moment, the presidential campaign is very unclear. Iván Cepeda leads polling and is extremely unlikely not to make the second round. Who joins him is hard to see at this point, so the consultas will trim that field significantly.

While the Senate and Cámara will be decided by mid-March, this is only the first lap of the field for the presidential candidates. Some will fall out, others will consolidate their position and things will start changing throughout the spring until the May 31st first round.