Teachers striking on Calle 26 were dispersed by police with water cannons and tear gas. Photo: Angie Ochoa

May and June have seen protests throughout the country with teachers’ strikes in major cities and civil action in Chocó and Buenaventura.

Less than halfway through the year, Colombia has seen a significant number of civil and union strikes across the territory. On the Pacific coast, civilian strikes in Chocó and Buenaventura led to disruptions in commerce and trade, while ongoing teacher strikes in the capital and other major cities have caused transportation and mobility disruptions.

Teachers’ strike

The Colombian Federation for Educational Workers (Fecode) and the approximately 350,000 workers it represents declared a general strike on May 11, leaving over 8 million public school students out of the classroom.

While negotiations have made some progress, at the time of going to print, the strike action showed no signs of abating. Fecode have announced that the strike will continue until they are able to meet directly with the president and present their demands.

“Last night the education minister appeared on television saying the negotiations were very close. That is not true, and it has altered the teacher’s mood,” elementary school teacher Angie Ochoa told The Bogotá Post on June 13.

“Of course, as teachers, we’d like [the strike] to end soon. However, we hope to reach a good agreement,” she added.

Protesters have put pressure on the government with massive demonstrations across major Colombian cities. The epicentre has been the capital, where tens of thousands of teachers and sympathisers have caused general transportation disruptions. They intend to continue using pressure tactics such as those seen in Chocó and Buenaventura, including road blockades and marches.

The striking teachers are disgruntled at what they see as the government’s failure to keep its promises after a 2015 strike. Initial negotiations spilled onto the streets because the Ministry of Education claimed not to have enough funds to deliver on the previous agreement.

One point of contention is pay, with teachers demanding the same salary level as other state workers. A salary increase totalling 8.75% was announced on June 5, but the strike action continued. Fecode president Carlos Rivas stressed that the protests “are not only a salary issue; we are demanding food, transportation and infrastructure for the children. We are fighting for the quality of education in Colombia.”

His words are echoed by teachers on the street, as Ochoa says: “We are fighting for an increase to the sistema general de participaciones, which will be in charge of allocating the funds that will finance education for the next ten years.”

Specifically, the teachers are still fighting for a reformed educational policy, a unified charter to regulate career paths, economic sustainability and improved health care services.

Tensions flared on June 5 when President Santos insisted “the teachers must make up the classes in order to receive their salary for the days they didn’t work.” Rivas countered that the teachers “have always made up lost time and more in previous strikes.”

Fecode also denounced the heavy handed police response at the last demonstrations along Calle 26, where they were forcefully dispersed with high pressure water tanks by riot police (known as ESMAD).

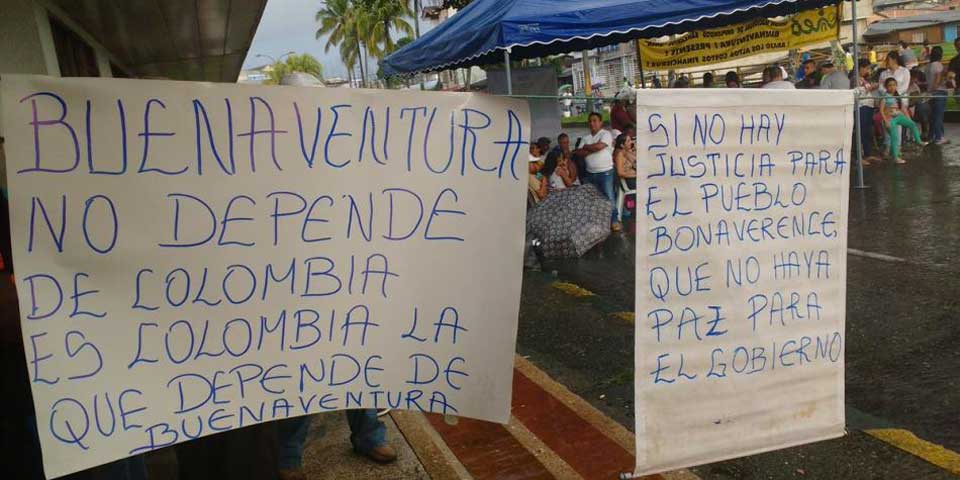

Placards in Buenaventura demanded the country’s attention.

Chocó and Buenaventura

Meanwhile, weeks of protests in Chocó and Buenaventura have come to an end as the government reached agreements with both communities.

The Chocó deal was announced on May 27 after 18 days of civil disobedience and includes commitments to improve the quality of life for Chocó inhabitants, including investment in transport and health infrastructure.

Thousands of people joined the Chocó demonstrations which paralysed commercial activities throughout the department.

On June 5 leaders in Buenaventura reached an unprecedented COP$1.5 billion agreement with the government. The funds are to be allotted to the newly created Fondo de Patrimonio Autónomo para Buenaventura.

Fighting for basic infrastructure, healthcare and water rights, residents of the port city effectively shut down the country’s biggest port, leading to an estimated COP$300 billion in economic losses. The losses from the transportation industry alone were estimated to be COP$63 billion, just in the idleness of transport lorries.

Their efforts led to important gains to be incorporated into a ten-year development plan. One of the crucial points was water management. According to Jaime Alves, research affiliate at the Centre for Afro-Diaspora Studies at the Universidad Icesi in Cali, 64% of the 390,000 inhabitants live in poverty, and most do not have access to drinking water.

Complete access to potable water has been promised to the community in the next two years. Other citizen demands that will be funded include improved access to healthcare and a seven-year education plan to guarantee coverage and quality education to 100% of the population.

An important part of the deal calls for the investigation into human rights violations committed by the police and soldiers against the protesters.

Human rights defenders including Amnesty International, denounced the “excessive use of violence by the ESMAD against those participating in the general strike.” Police tactics included the use of tear gas against children and elderly people.

While residents will await for the promises to be fulfilled before declaring victory, they called the deal a major and historical moment not only for the people in Buenaventura but for the black movement and people in Colombia.