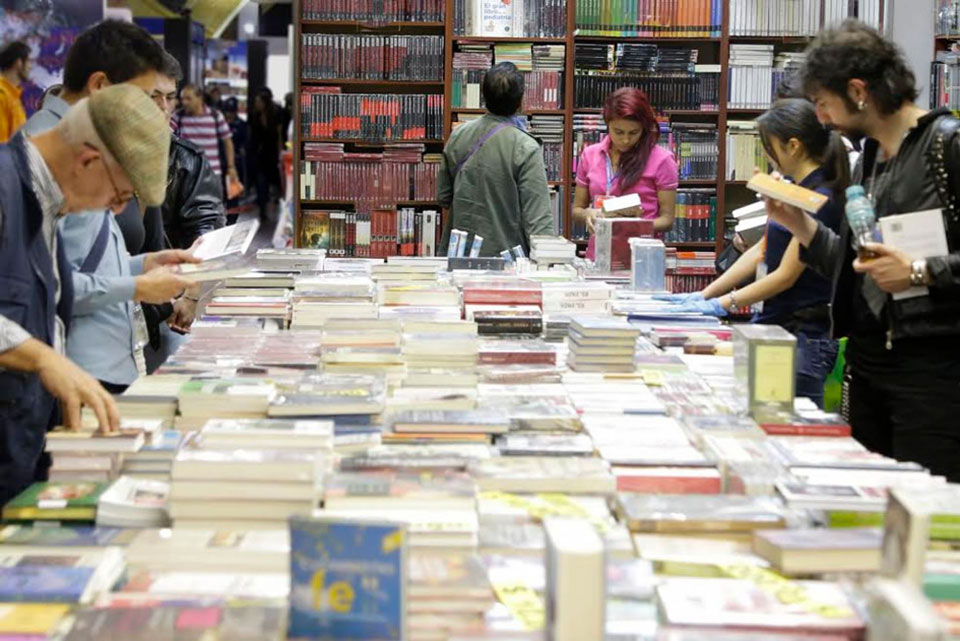

FILBo 2017, the 30th edition of Colombia’s biggest book fair will run from April 25 to May 8.

Bookworms that we are, we open the pages of FILBo 2017 and say bonjour to the continent’s biggest celebration of reading. This year it’s celebrating 30 years, and we ask how to get the most out of the region’s biggest book fair? Christopher Outlaw gets some expert opinions.

This city has been called “the Athens of Latin America” by way of analogy to the Greek capital as a centre of classical learning (if sadly not to its Mediterranean climate). The epithet really comes into its own at this time of year when the Bogotá International Book Fair – universally known by its Spanish acronym, FILBo – takes over the whole of the massive Corferias exhibition centre. This year’s edition, FILBo 2017, will run from April 25 to May 8.

What is FILBo?

FILBo is one of South America’s largest book fairs, a wonderland for bookworms to peruse and buy among the hundreds of stalls and millions of books while attending talks and workshops with their favourite authors. But it’s far more than that. It’s a space for broad discussions and the democratisation of reading; a window into unknown cultures; a fun day out for families with activities for children and teenagers; a draw for lovers of music and food; and a chance for journalists, illustrators, editors and other industry professionals to meet and exchange ideas.

Put simply, FILBo 2017 is the capital’s biggest gathering of national and international creative genius.

What is special about FILBo 2017?

FILBo is marking its 30th birthday this year with a guest list bursting with world-famous names, Colombian talent and a packed programme of events.

Big names this year include two Nobel laureates: South Africa’s J.M. Coetzee and V.S. Naipaul from Trinidad and Tobago. Coetzee’s writing, while often rooted in apartheid South Africa, deals with universal themes and includes historical and psychological novels as well as fictionalised autobiographical and experimental works. Naipaul, too, merges fiction with autobiography and documentary. He is known for his keen sense of observation and was described by the Swedish Academy as “a literary circumnavigator”. He has written novels set in almost every continent. Fans will have the opportunity to hear them talking about their work and queue up for book signings.

Each year a country is invited by FILBo as a literary guest of honour, with the chance to showcase the best of its culture in the Colombian capital. This year’s invitee is France, to coincide with the Año Colombia-Francia.

France is this year’s special guest as part of the Año Colombia-Francia.

Alongside a formidable selection of Gallic literary and artistic panache, the French Pavilion – designed to evoke the je ne sais quoi of a Lutetian boulevard – will house a restaurant, Parisian café, and no less than three book shops. Magnifique!

Literature for children and young people has always been important at FILBo. However, 2017’s guest country is keen to give equal emphasis to each category, with children’s and young adult literature being promoted separately for the first time. Among the French contingent are a number of high profile illustrators and graphic artists such as Benjamin Lacombe, who published his first graphic novel, Cerise Griotte, at the age of 19 and has since written and illustrated dozens of works by himself as well as authors as diverse as Lewis Carroll and Edgar Allan Poe.

FILBo’s 30th is one of several important anniversaries in 2017. Examples in Colombian literature include it being 50 years since the publication of Gabo’s seminal chef d’oeuvre One Hundred Years of Solitude (as celebrated on the new 50,000 peso note), and 150 since Jorge Isaac’s María (check out your old 50,000 notes).

What and who not to miss this year:

Naipaul and Coetzee will undoubtedly be at the top of many fairgoers’ lists but, with a veritable mélange of over 300 novelists, journalists, illustrators, graphic designers and academics invited, there are plenty more names to choose from.

A weighty Francophone voice will be that of Pierre Lemaitre. Better known for his crime fiction, he won France’s prestigious Prix Goncourt in 2013 for his World War I epic Au revoir là-haut (Goodbye Up There). There’s a pertinence here in the book’s focus on the difficulties of post-war life for young former soldiers.

Indeed, international names abound. FILBo 2017 press officer Diego Aristizábal’s recommendations include Spanish writer Julia Navarro and US novelist Richard Ford as well the latter’s compatriot John Katzenbach, who will be on hand to talk about (and sign) his psychological thrillers.

Thousands of book lovers will descend on Colferias over the duration of FILBo 2017.

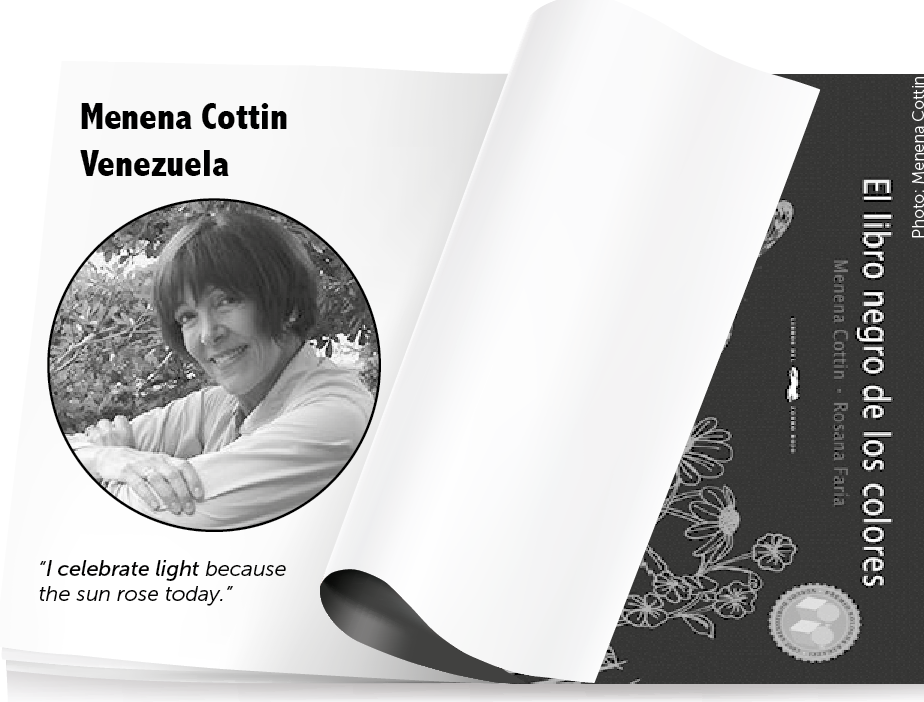

Among interesting themes at this year’s FILBo Fringe of talks and debates are Post-Conflict and Reconciliation; LGBTI; Migration; and Disability. Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos will discuss democracy in times of change; Chilean graphic designer Gabriel Ebensperger (see across) is to explore the idea of turning fear into art; writers from Mexico and Cuba will talk about emigrating and fleeing; and Venezuelan Menena Cottin (see below) will present her book about a blind child’s perception of colour.

We asked Alberto Gómez from Casa Librería Wilborada 1047 and Camilo Hernández from Los Andes University for their top tips among the Colombian speakers at FILBo 2017. They mentioned much lauded narrative journalist Alberto Salcedo Ramos; Luis Noriega, 2016 winner of the Gabriel García Márquez Short Story Prize; Pablo Montoya, who will be sharing his Cuaderno de París in a nod to this year’s guest country; and one of Colombia’s most outstanding illustrators, Ivar da Coll as well as younger writers like novelist and blogger Daniel Ferreira, and Gloria Susana Esquivel, a journalist and poet.

The fair is naturally a must for the more bookish among us, but organisers and FILBo veterans alike urge visitors not to forego the other academic, gastronomic, professional, and musical temptations.

Libros para comer (Books for Eating) promises a series of presentations in which chefs and authors will present their work before offering a culinary masterclass.

¡Que viva la música! is the title of Andrés Caicedo’s 1977 cult novel lovingly set in the febrile world of 1970s Cali. It’s also the name of FILBo 2017’s cycle of musical events, in recognition of it being 40 years since the book’s publication. The programme will interweave poetry and art with genres from rock and jazz to salsa as well as a celebration of Bob Dylan, who finally deigned to accept his Nobel Prize at the end of March.

How to enjoy a day out at FILBo 2017:

You may believe that all the good stuff happens at the weekends, but au contraire! Coming during the week is a great way to avoid the infamous FILBo mêlée and there’s a plethora of things to do besides browsing the stalls. Come en masse by public transport if you can, there’s even a TransMilenio stop called Corferias.

Don’t forget to check the FILBo 2017 programme of over a thousand events and – as Aristizábal says – go “with an open mind [and] be ready to get stuck in, go to talks, get your books signed, chat to people and let yourself be surprised.”

FILBo 2017 new faces of note

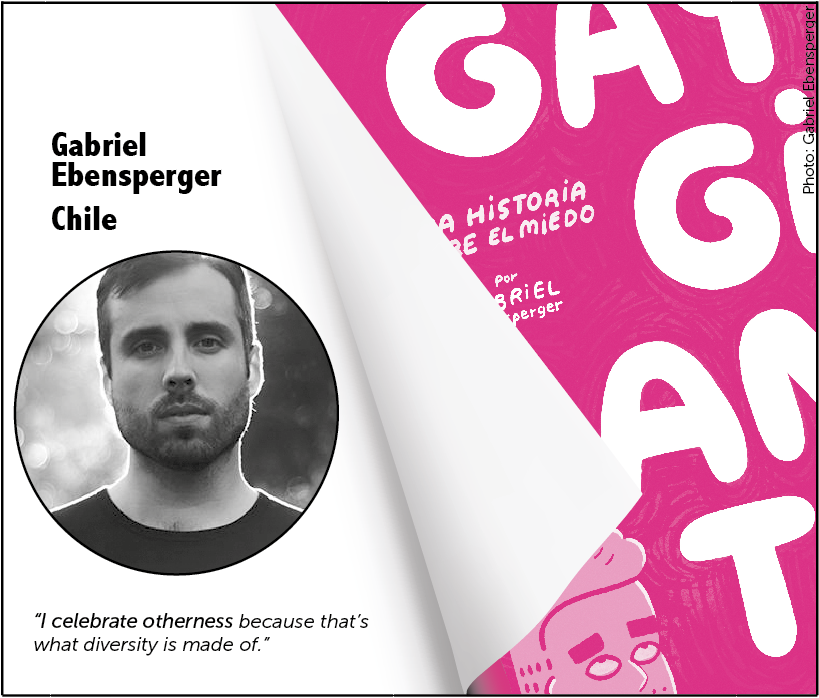

Three first-time invitees from across the continent speak to us about otherness, surprise success and seeing without seeing. To promote the festival, each writer was asked what they celebrate through their work.

Graphic designer, illustrator, writer, photographer and blogger Gabriel Ebensperger says he was born an artist. His métier complements text with pictures, since “images give intensity”. He likes bright, bold colours and describes his work as “visual, but also narrative, adventurous and sarcastic.”

Graphic designer, illustrator, writer, photographer and blogger Gabriel Ebensperger says he was born an artist. His métier complements text with pictures, since “images give intensity”. He likes bright, bold colours and describes his work as “visual, but also narrative, adventurous and sarcastic.”

This will be the Chilean’s first time both in Colombia and at a major international literary festival. He’s coming without expectations, “the best way to travel.” At FILBo, he’s excited about the presence of other artists, in particular Frenchman Benjamin Lacombe.

In Bogotá, Ebensperger plans to talk about his first graphic novel, Gay Gigante: Una historia sobre el miedo (Gay Giant: A Story about Fear). The somewhat autobiographical title character is not literally a giant. The term refers rather to his endless feeling of “never being able to go unnoticed … of always being strange.”

Through Gay Gigante, drawn with poignant simplicity and much humour in striking magenta and white, Ebensperger lambasts “heterosexual privilege,” internalised homophobia, and those who give lip-service to diversity. He exposes the challenging reality of growing up and being gay (especially) in a machista society while also lampooning current affairs and the frustrations of modern urban life.

Alongside pictorial diatribes against sexism and pointed pastiches of prejudice on dating apps, in the Chilean’s Gay Gigante work you’ll find emojis from grandma and tips for dressing up as Princess Leia.

Published in book form in 2015, Gay Gigante started “very organically” (and continues) as a blog – Ebensperger’s way of creating art for himself when working as a graphic designer meant constantly drawing for other people. He then took a sabbatical year to complete it, his first experience of authoring a work entirely by himself. He didn’t set out to tell a particular story, but now sees the book’s purpose as fighting homogenisation and generating empathy among the “un-oppressed” majority who have little reason to consider the experience of minorities. He wants everyone to recognise “the otherness inside themselves.”

The book has garnered both praise and awards such as Chile’s Medalla Colibrí, which celebrates literature for young people, but its creator says “the best thing is hearing [from readers] that you helped them feel less alone, that you cheered them up”. Not wanting Gay Gigante to swallow him or to overexploit his character’s success, Ebensperger’s plan for a second graphic novel is “not exactly Gay Gigante 2”. He also wants his first book translated into English and French.

Ebensperger grew up during Chile’s transition from dictatorship in the 1990s. Reflecting on that process and with a message for today’s Colombia, he affirms art and literature as “tools of historical, emotional, and social record (…) forms of protest against violence, cynicism, and lies.” If you ask me, the world needs more of both in 2017.

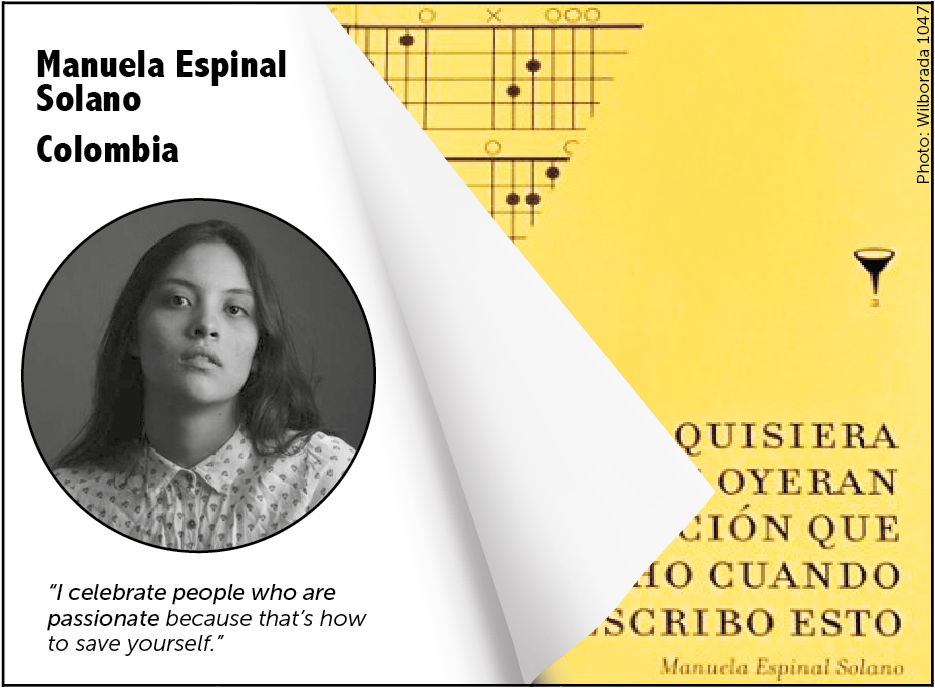

“Wow!” was this young writer’s reaction to being invited to FILBo. “Everything has been a surprise since the publication of [my] book, but that was one of the biggest,” she said.

“Wow!” was this young writer’s reaction to being invited to FILBo. “Everything has been a surprise since the publication of [my] book, but that was one of the biggest,” she said.

Manuela Espinal Solano’s first novel was published last year when she was just 18. Gracious and eloquent on the phone, she is modest about her talent, previously regarding FILBo as a space only for established literary figures. Now studying communication and journalism in Medellín, she’s been writing since she was a child, especially songs.

Quisiera que oyeran la canción que escucho cuando escribo esto was entered into a competition under the much shorter title of Herencia (Inheritance). Espinal admits to being nervous at the idea of submitting the story, and it didn’t win. Luckily, Héctor Abad Faciolince – a grandee of modern Colombian literature to whom she’s immensely grateful – read the work and asked to publish it. His publishing house suggested she choose a longer title.

A story rooted in her own experience, If only you could hear the song I’m listening to while I write this, recounts a girl from a musical family and her relationships with her mother and grandmother. According to Espinal, her book is “a real story I wanted to tell. [All I’m trying to do] is make people feel like they’re really there.” She’s received encouragement from teenagers who relate to the narrative as well as older readers who “feel moved” by her writing.

For Espinal, singing and writing are inseparable. “When I’m writing, I start to criticise what I’m doing and think ‘I’d be better off singing,’” and vice versa. She loves both, but her ambitions lie squarely with writing. “The challenge now is to find my own identity as a writer,” she says.

“I landed in the midst of literature and without knowing it or planning it, I got into children’s books.” Generously speaking to me early one morning from her home in Caracas before catching a flight, the loquacious Menena Cottin’s joie de vivre would stay with me all day.

“I landed in the midst of literature and without knowing it or planning it, I got into children’s books.” Generously speaking to me early one morning from her home in Caracas before catching a flight, the loquacious Menena Cottin’s joie de vivre would stay with me all day.

The Venezuelan – who considers herself more of an illustrator than an author after a 30 year career as a graphic artist – describes herself as an “intuitive” writer. “My creative work [deals with] philosophical themes (…) I try to find the simplest way of expressing the message.”

Her most remarkable work is The Black Book of Colours, which has been translated into 16 languages. What is now an award-winning book started as a couple of pages, written for herself, on which Cottin imagined herself as a blind child, Tomás. “If I were a blind child and my friend said ‘the sky is blue, let’s go outside and play’, how would I understand ‘blue’?” In The Black Book Tomás’s blue is the sun warming the top of his head on a clear day and he goes on to describe all the colours by how they feel, smell, sound or taste.

The Black Book of Colours has “few words but much content.” Typically producing both images and text for her books, Cottin didn’t illustrate her most celebrated publication. Observing another artist produce the drawings was challenging but rewarding – “it allowed me to see myself as a writer.” The innovative black-on-black illustrations use a special ink to create a slightly raised, tactile picture, with the text in both white lettering and braille.

Some editions have been criticised because the braille text is not raised enough for a blind person to read easily. But other versions use a different technique to create true braille and, according to Cottin, that’s not the point. For her, “the book has fulfilled its mission to raise awareness among a great many sighted people” of the challenges blind people face navigating a world which they cannot understand visually. It’s a source of “great satisfaction.”

A related work is Cierra los ojos que vamos a ver (Close Your Eyes Let’s See), first presented at Cartagena’s Hay Festival in 2013. It is the published correspondence between Cottin and Lucero Márquez, a blind reader whom the author first met at The Black Book’s original launch in Mexico, including Cottin’s non-visual description of a trip to the Himalayas and Lucero’s own perceptions of the world she cannot see.

FILBo 2017 will be Cottin’s first and she’ll be taking part in several events including an activity for children based on the extraordinary Ana con A, Otto con O – also available in the form of an app thanks to help from her son. In a Spanish linguistic curiosity, Ana, Otto and Pepe communicate in meaningful dialogues even though they can only speak using a single vowel. “Clara mañana!” says Ana, meeting Otto one bright, sunny morning. “Con sol!” he replies. Through replicating word games like this, Cottin hopes children will learn to appreciate and be proud of their language.

Menena Cottin really makes you realise the “infinite potential” of books.

By Christopher Outlaw