High-flying maneuvers, a roaring audience and lots and lots of spandex: Lucha Libre–Latin America’s answer to professional wrestling–may seem to outsiders to fall anywhere between martial arts, comic convention and circus show. Reminiscing of ‘The Golden Years’ when thousands were flocking to the arenas, a committed core of dedicated athletes is now fighting to bring Colombia back in the ring. What are the odds of it coming back?

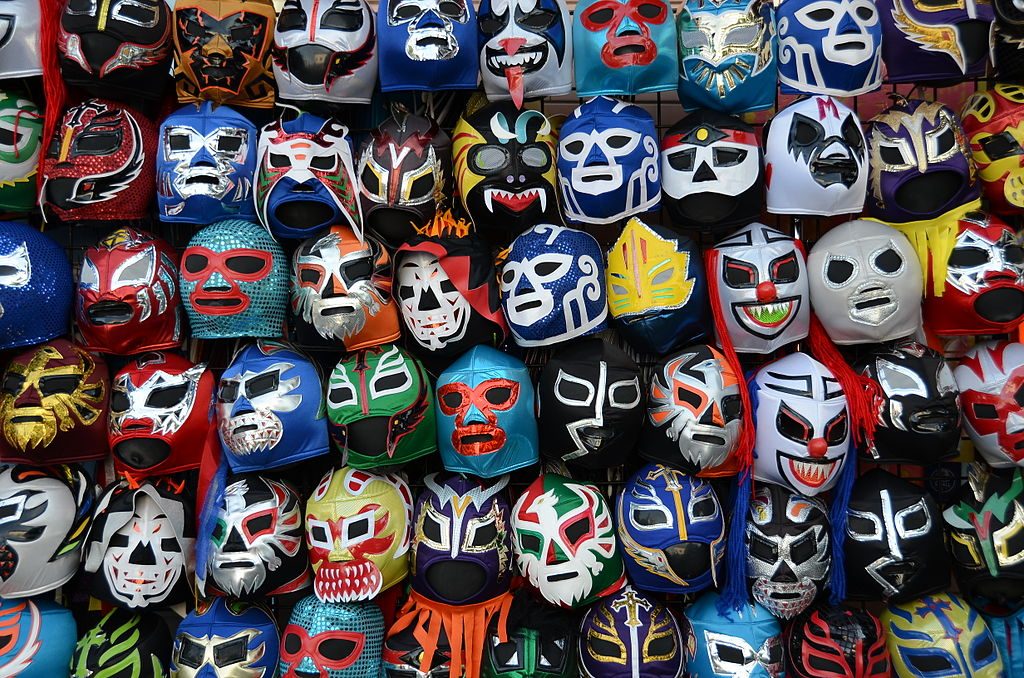

Around the world, professional wrestling is a shared passion of Mexico, the United States and Japan – three countries rarely put in one group when it comes to their culture. For novices to the flamboyant world of pro-wrestling, the Mexican variant, lucha libre, is easily identified by the colorful masks that fighters are sporting. With an emphasis on aerial maneuvers rather than muscle force, this style of fights follows highly choreographed battles of good (técnicos) versus evil (rudos) – the latter sometimes representing unpopular politicians or narcos. And without going deeper into common story lines or cheers you witness in fights involving women, drag costumes or micromen, it is safe to say that visitors should generally not expect political correctness.

El Jaguar, El tigre, Hércules Negro: These are not to be confused with alias names of guerrillas or drug lords, but represent characters of Colombian professional wrestlers that achieved legend status in the sport’s golden era leading up to the 1980s. Back in these days, more than 10,000 spectators would flock to venues such as La Arena Bogotá to witness their favorite fighters catapulting themselves on their opponents in complex aerial maneuvers. Today, this cheering crowd has dwindled and rarely hits more than 300 people, unless superstars from abroad are invited in the ring.

“There have been times when (…) I try to give up, because the truth sometimes you lose money,” says José Luis Espinoza, creator of the Novato de Oro Championship in Colombia. He charges about $15,000 COP for a ticket, not enough to be able to pay the fighters a salary that would allow their athletic passion to become a professional career. But in our interview, he still seems more determined than ever to persevere. “I have faith that our sport will return to what it was before, when there were 4 large companies and international fighters came here to compete against Colombians”.

Indeed, there are signs that the sport deemed knocked out is slowly lifting itself from the ground again. Earlier this month, an evening with top fighters from Mexico was able to attract 8,000 people, according to organizers. In the meantime, a new generation of athletes from Colombia is dedicated to a strict training regime despite the challenge of making ends meet. People like Najamura Jr., a tattoo artist and hospital stretcher bearer during the day, who squeezes in four hours of training after his work every day.

Why do they keep fighting to revive this sport, despite all these challenges? For José Luis Espinosa, it is the unique “amalgam” of the fights that keeps fascinating him, the “extraordinary combination of grappling and defense, of agility and dexterity, and of something you have in the blood”.

But a key challenge will be not only to train a new generation of athletes, but to have professional management back in the game. According to expert Orlando Jiménez, the old league of superstars “did not teach another generation to do the business” – and the promotion companies gradually died.

Furthermore, promoting and marketing a sport that has long lost all but the most diehard fans will not be easy. Yet in the world of sports, it would not be the first instance of Colombian love (and success) for unexpected disciplines: For example, foreigners are often surprised to find out that, besides the ubiquitous football and cycling, Colombia is one of the leading nations for inline skating. While the niche of speed (inline) skating is not part of the Olympics, Colombia’s Pedro Causil anecdotally traded wheels for blades earlier this year to become the first ever South American to take part in the speed skating finals of the Winter Olympic.

Lucha Libre is a sport that usually knows every battle move carefully choreographed, and winners and losers are set before each match. Yet in Colombia, the last battle currently fought by its most devoted fans is everything but certain. For those who thought Colombian lucha libre has received its fatal strike in the global arena, a surprise comeback might be in the making.