The exhibition focuses on Caldas’s map-making and scientific skills.

‘Ojos en el Cielo, Pies en la Tierra’ at the Museo Nacional focuses on the astronomical and map making skills of Francisco José de Caldas – better known as one of the heroes of Colombia’s independence.

‘Patriot’ and ‘martyr’ are the two words that history books most commonly attach to Francisco José de Caldas, a Colombian lawmaker and scientist executed in the back by Spanish royalists in 1816.

My son, seven years old, is fascinated by this gory tale as we tour an exhibition in Caldas’s honour at Bogotá’s National Museum.

‘Why didn’t he jump up in a tree? Or run in a zig-zag to dodge the bullets?’ he asks. I explain that real life rarely plays out like a Marvel comic movie and, anyway, the unfortunate Caldas was probably tied up at the time.

But, thinking it through, Caldas was every inch a superhero. The Popayan-born criollo trained as a lawyer but over his shortish life – 48 years – morphed into an engineer, inventor, soldier, journalist, naturalist, meteorologist, mathematician, astronomer and map-maker.

Related: Going back to the start: A young Botero returns home

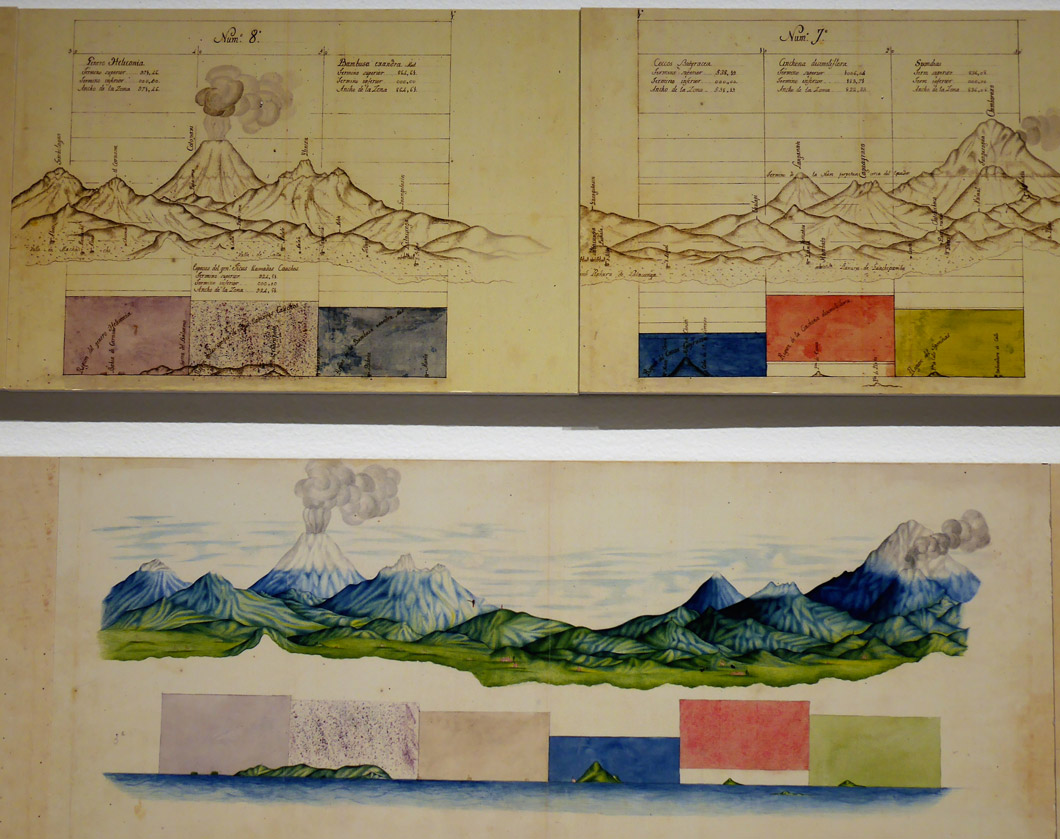

It’s the last two aspects of the payanés life that form the basis of Ojos en el Cielo, Pies en la Tierra at the Museo Nacional. The display of maps and diagrams which had been hand-drawn by Caldas (or under his supervision) are united with the cartographic and astronomical instruments of the era which the industrious – and largely self-taught – polymath plotted the rich geography of the New Kingdom of Granada, as pre-independent Colombia was known.

This corner of the world was something of a backwater in 1768, the year Caldas was born, and Popayan the back of beyond. But the young criollo grew up with ‘a thirst for knowledge that devours’, as he later wrote.

Feet on the ground

One of his passions was geography and putting some sense of order in the tumble of mountains and ravines that made up his homeland, where hiking the Andean landscape he very much had his feet on the ground – pies en la tierra.

He managed to get hold of early surveying equipment such as compasses and octants and used their user-manuals and his own knowledge of maths to learn to triangulate positions and draw up maps and the very first profiles of the mountain ranges.

An early surveying instrument of the type used by Caldas in the early 1800s.

Of course, in this pre-GPS era navigation and mapping was linked to the stars and planets so he also had his ‘eyes on the heavens’ – ojos en el cielo – skills which in later in life would lead him to run Bogotá’s astronomical observatory.

And as was common at the time for scientists, Caldas had a holistic view of on the natural world around him and studied botany and how climate and vegetation changed with altitude. This he measured using his own invented technique of hypsometry which relies on the water boiling at lower temperatures at higher altitudes (which also explains why it’s hard to make a nice cup of tea in Bogotá where the kettle sings at 92°C).

It’s this scientific and inventor side of Caldas that the exhibition aims to promote, explains curator José Antonio Amayá, himself a professor of the science history at the Universidad Nacional.

‘Everyone learns at school learns about Francisco José de Caldas the independence hero. But he was so much more,’ explains Dr Amayá. ‘He was the first person to really investigate and try and describe the physical spaces and natural order of the new kingdom.’

Caldas’s scientific skills captured the attention of the Spanish botanist José Celestino Mutis and German geographer Alexander von Humboldt – the heavyweight naturalists in South America at the time – and he joined them on several scientific expeditions in the early 1800s.

Caldas also drew the first profiles of Colombian mountain ranges with accurate altitudes which he calculated using his own techniques of boiling water.

But as a New World-born criollo, Caldas also experienced first-hand the discrimination by the Spanish colonial rulers who insisted, for example, that only Europe-born surveyors could map the New World. Caldas did it anyway, though often secretively.

Such petty slights by the colonists engendered the independence movement, and in Caldas the ideology that the local-born had as much right to study and map their environment as the Europeans. He became a key figure in the revolution movement as editor of the political news-sheets, then drafted in to the revolutionary army as an artilleryman and military engineer, constructing fortifications for the rebel armies, plans of which are also on display.

His untimely death came in 1816 after capture by Spanish royalist forces and execution by firing squad in Bogotá’s Plaza San Francisco (today’s Parque Santander).

Legend has it that bystanders begged the Spanish rulers to ‘spare the life of the scientist’, but that the executing general rejected the pleas declaring: ‘España no necesita sabios’: ‘Spain does not need the wise’. Thus, the payanés earned his posthumous sobriquet ‘El Sabio’: Caldas the Wise.

No magic powers there, though. Just hard work, vision and passion. What more does a superhero need?

INFORMATION

- The exhibition Ojos en el cielo, pies en la Tierra. Mapas, libros e instrumentos en la vida del Sabio Caldas runs from December 7 to February 24, 2019, at the Museo Nacional, Carrera 7a #28-66, Bogotá, 10am to 6pm. Entrance is free.

- For more details on the life of Caldas, you can also visit the Casa Museo Francisco José De Caldas, Carrera 8 #6-87, Bogotá, open 10am to 3pm. Entrance is free.