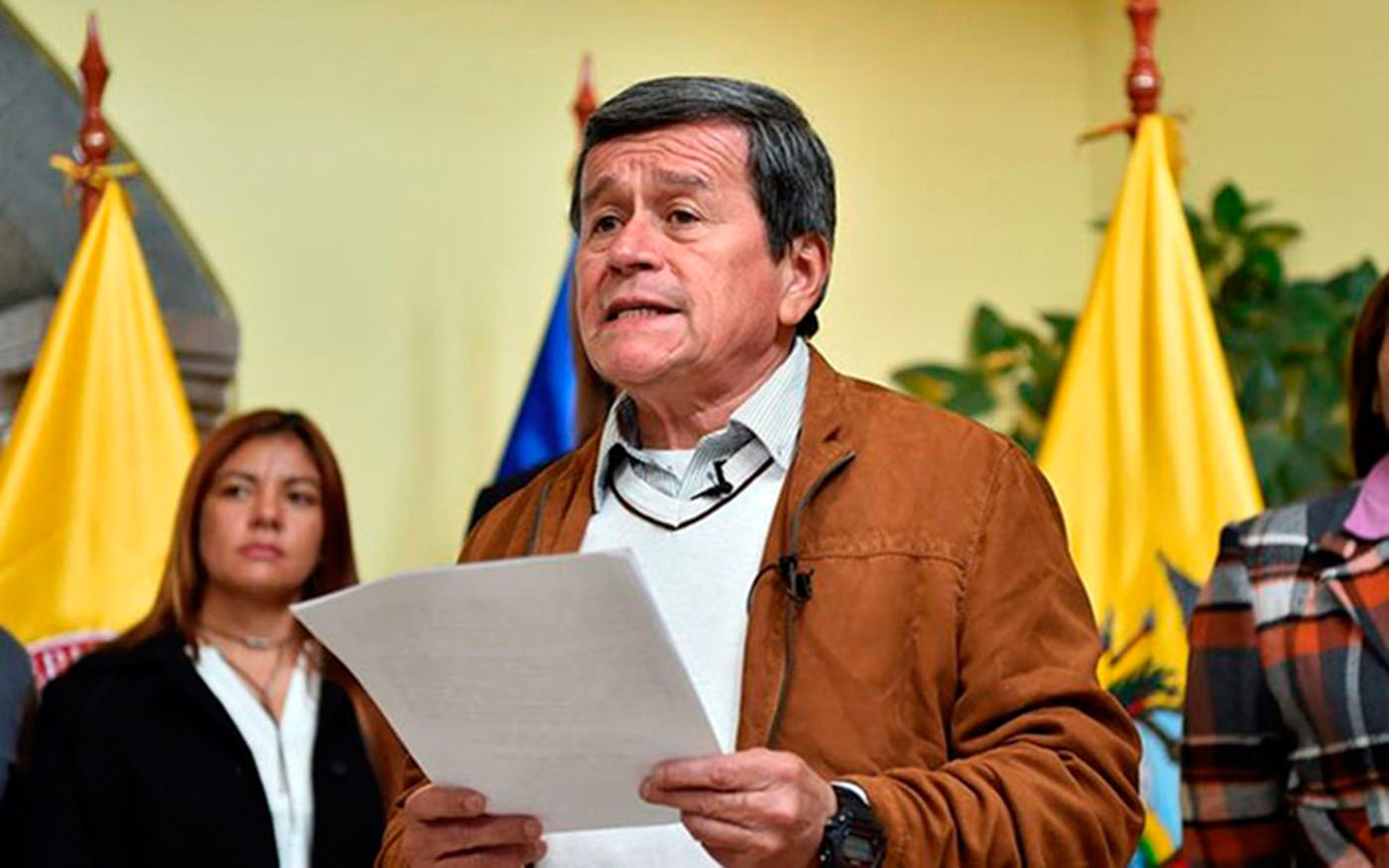

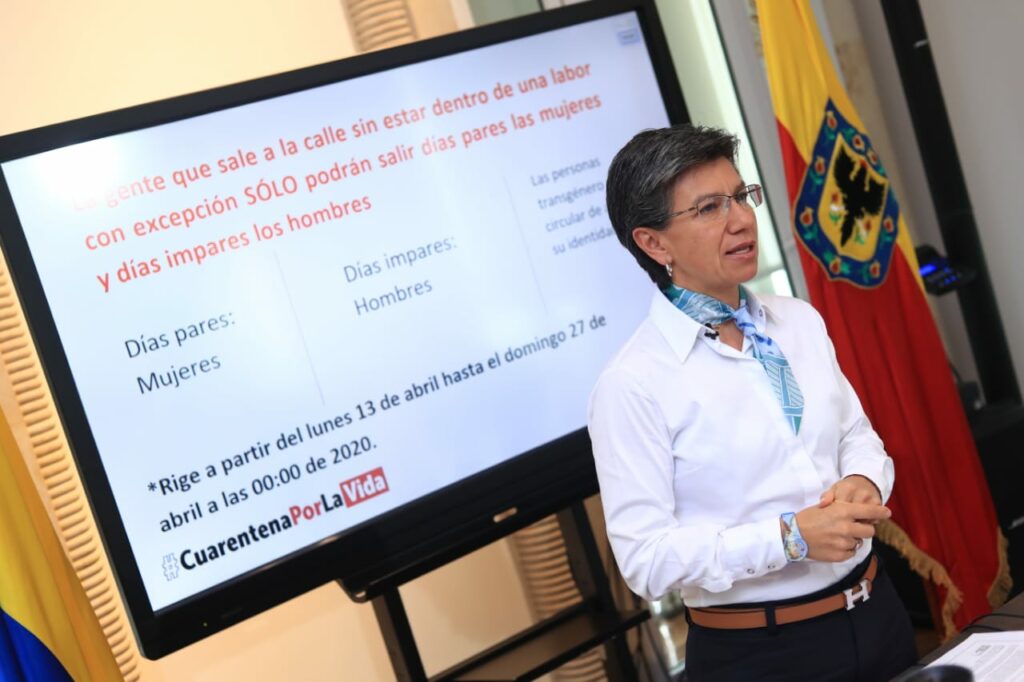

Claudia López announces gender-based restrictions to mobility.

López’s latest announcement regarding the quarantine in Bogotá, which is currently set to continue through April 26, comes with Decree 106, which includes pico y género. The attempt at a catchy name for the new policy is meant to hark back to pico y placa, the traffic-control policy in which car traffic was restricted according to the odd or even-numbered ending of a car’s plaques.

When applied to gender, the policy functions similarly. Women will be allowed to circulate to perform essential tasks – ie grocery shopping, going to the bank, and going to medical appointments – on even-numbered days, while men will be permitted to do so on odd-numbered days

Read our latest coverage on the coronavirus in Colombia

The policy starts on Monday, April 13 and will be implemented through the end of the current quarantine period, April 26. Anyone else who is not acting in accordance with the policy will be fined 1 million pesos.

To make things easier on the public, the City of Bogota’s website published a list with the days from April 13 to April 26, accompanied by the gender that is permitted to go out on that day. Healthcare workers, civil servants, delivery people, and other essential workers, are exempt – as well as people walking their dogs.

What other additional measures have been announced?

Beyond pico y género, Decree 106 includes two major additional policies. Bogotá’s taxi drivers, who are permitted to circulate under certain restrictions, must keep an official record of all of their passengers. At the end of the day, taxi companies must report the passenger name, origin and contact details to the local authorities.

Alcohol sales are now limited to one product per person, and shops also need to keep a record of them. Additionally, supermarkets and markets will open special queues exclusively for seniors and healthcare workers. The decree also contains additional measures to protect delivery workers, such as disinfecting workplaces and banning gatherings of more than five workers.

Why not pico y cédula?

Pico y cédula, would allow people to leave their homes for essential errands depending according to whether their cédula, or identity card, ended in an odd or even number. However, in her announcement of pico y género, López explained that pico y cédula is very difficult to control.

Many other cities in Colombia, including Medellín, Cali, some cities and towns in Cundinamarca, Ibagué, Tunja, Santa Marta, Cartagena, and Popayán have all implemented pico y cédula within the quarantine. Popayán did so from the outset on March 24, while others like Cali, implemented the measure earlier this week.

Where else is pico y género being implemented?

Neighbouring Panama and Peru have been implementing pico y género style quarantine measures since last week. Panama was the first to announce its new policy on April 1 with Peru quickly following suit on April 2.

In El Espectador, Panamanian epidemiologist Xavier Sáez-Llorens explained that gender really didn’t have anything to do with the rationale behind the government’s new policy. The reason gender is being used, he explained, is because separating who can and cannot go out by gender is “one of the easiest ways to take control” and strengthen the effectiveness of the quarantine.

Pico y género and the trans and/or gender-nonconforming communities

Theoretically, gender should give authorities more obvious, visible markers with which to enforce a policy meant to reduce the number of people on the streets at any given time. However, it is important to note that this is not always the case: An individual’s perceived gender does not always match their gender identification, nor does it always match the sex listed on their identification card.

López did her best to acknowledge the issues this would cause for the city’s significant trans community, stating that trans-identified individuals should follow the policy according to the gender with which they currently identify.

Colombia Diversa, a nonprofit that aims to champion the rights of LGBT people in the country, quickly responded to obvious concerns surrounding the measure, with a series of reminders to the community. These include:

- The mayor’s office has clarified that trans people can leave their homes on the days corresponding to their gender identity.

- Several reminders regarding police, who must respect trans identities when enforcing the new policy and who should not ask to see people’s identification cards.

- The group called for police and other governing bodies to collaborate in order to monitor police enforcement of pico y género on a daily basis.

Similarly, one of Bogotá’s most active trans-rights groups, the Red Comunitaria Trans, responded to the decree with an open letter titled “Tenemos miedo” or “We are afraid.”

The letter explains that though the organisation understands the importance of quarantine in mitigating the threat of COVID-19, it rejects “measures that restrict mobility based on the criteria of sex/gender” and opposes putting the police in charge of gender policing.

This, the letter goes on to say, will put trans individuals in danger, perpetuating a police culture of violence against trans people. Finally, the letter demands that the city create an official reporting system for people who experience harassment or violence in these circumstances, as well as a decree that explicitly states how police with be punished if they abuse their power.

The organisation published the letter on social media, followed by historical footage of 2015 police violence against trans individuals in the city, and several artworks accompanied by the hashtag #lapolicianomecuida (the police don’t take care of me).