The Parque Nacional has finally reopened after months of restoration work, giving a new lease of life to Eastern Bogotá

Following an occupation by an Indigenous Embera population, the Parque Nacional was closed for weeks on end to allow the area to recover. The rains of La Niña barely arrived but enough fell to spur an impressive regrowth and the park is green once more.

The park has been progressively opening over the last few weeks, with the mid level opening up first for dog walkers and families, while the lower levels have remained off limits right up until this week.

The grand reopening comes along with a mini Christmas market and lights to encourage people back into the park. However, it’s come late, arriving just a week before Christmas. Given that many people will be leaving the city this weekend for the holiday period, traders and portrait artists etc are unlikely to be happy.

Still, better late than never and the lights are pretty nice, taking full advantage of its location at the foot of the cerros orientales.

The question now will be what the local government do with the park going forwards. The increased lighting is in place, but worrying signs are already popping up.

The sections that have been open for a month or so have already become open toilets for both humans and dogs. To some degree that’s understandable – the toilets haven’t been reopened and most remain locked.

Safety will likely be the litmus test though. There have always been security guards in the lower levels, but the park is open. At night-time that means plenty of hiding spots and of course those with long memories will recall the brutal murder of Rosa Elvira Cely in the park. There is still a moving memorial to that on the road down from the circunvalar.

Few in Bogotá will want to use the parque at quiet times if their safety can’t be assured. There is some precedent for this, with the parque bicentenario on the séptima above the 26 boasting 24/7 security. However, every alcalde says the same thing about park security and none have delivered. Will this be any different?

Where is the Park Nacional?

Properly known as the Parque Nacional Olaya Herrera, it is by some distance the biggest open green area in East-Central Bogotá. Running up from the Séptima into the Cerros Orientales, it is a valuable boon for densely populated barrios nearby.

The park is roughly split into three tiers, ascending upwards. The first level, entered from the Séptima, is an attractive park with walking paths and various facilities spread about it. Crossing the Quinta brings you into the second part with playgrounds dotted around large expanses of grass. From there, it melts into forest until arriving at the circúnvalar.

It boasts an assortment of sports facilities, with tennis and football chief among them. There are a number of tennis courts for full play and practice walls as well as five-a-side and full pitch football. The five-a-side pitches also see roller hockey and blind football events.

This being Colombia, there are speed skating tracks and volleyball courts too. Cyclists are a frequent sight, with the paved roads providing good climbing practice for roadies and kilometres of pretty gnarly tracks for MTB mudhoppers.

There’s also a theatre within the park and a pair of physical maps, one of Bogotá and its surrounds in the lower level and another of the whole country in the mid-parque. Education with your recreation is a thing here, with educational buildings in the higher levels that welcome school groups and the like for woodland walks.

Prior to the invasions, money had been invested in revamping the kids’ playgrounds, which are now replete with kids at weekends. Further up, the adult exercise areas see plenty of use too and groups of yoga or tai chi enthusiasts are all over the shop.

Sadly, roads still scar the park, making it less walkable than it could be. North/south, that’s the circunvalar at the very top or the quinta right through the middle. The calles are less problematic

Why were the Embera people in the park?

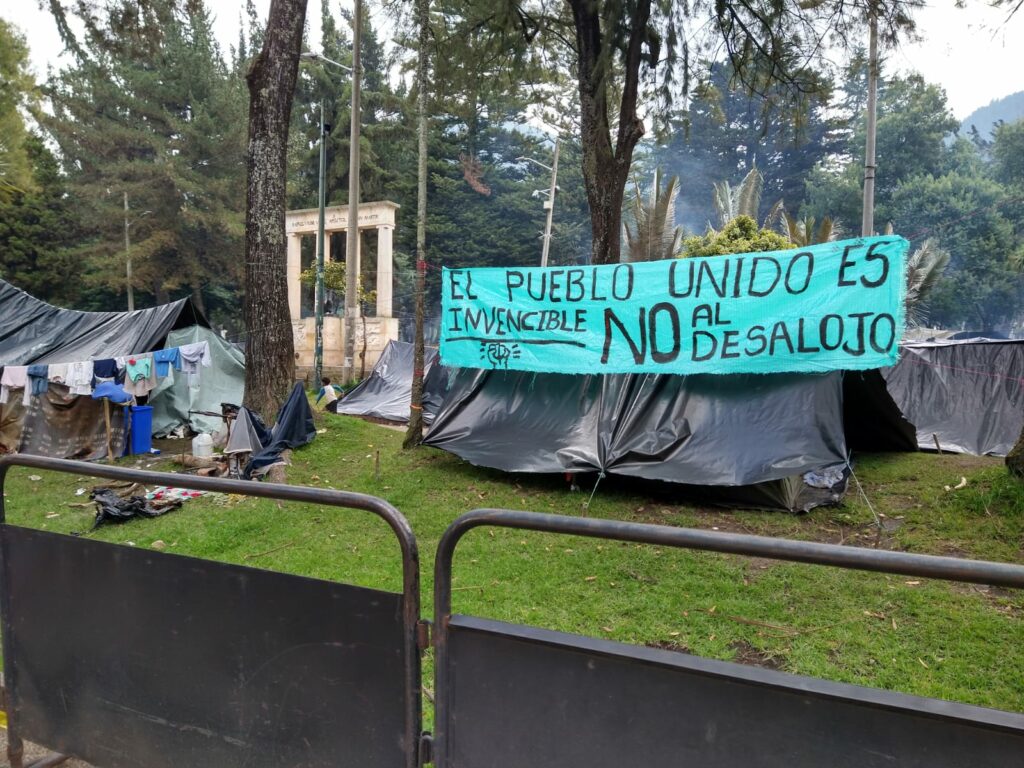

This particular part of Bogotano history stretches back over four years to October 2021, when the first Embera occupation arrived in the Bogotá park, fleeing encroachment by armed groups and illegal miners onto their ancestral lands.

They eventually returned after a year and half or so but some then returned again a few months later, with other groups joining them from elsewhere in the city. There are other, less visible for many, Embera communities in the city, especially in Parque Florida in the northwest of the city.

The second camp lasted a little over a year before again returning to their lands. While the first occupation garnered a fair bit of popular support, the second was marked by much less political and social solidarity and a lot more cynicism. Everyone suffered, from the Indigenous people themselves to local residents.

Most heartbreaking and prominent among the victims were the babies that have died in the squalid camp conditions. Dozens more children had to have medical treatment due to the dangerously unsanitary surroundings they were living in.

The camp was full of a great many highly vulnerable people, mainly children but also women at risk of domestic violence or forced to beg on the streets. Video footage of an abusive male partner against a young woman outraged many in the city, as did pictures of children placed in stocks as punishment.

This was no place for anyone to be living. Fresh water was another problem and plumbing non-existent. Instead, the Río Arzobispo took its place, turning it quite literally into an open sewer in the heart of the city. With water rationing coming in, that became more problematic.

Domestic animals lived cheek by jowl with the humans, creating further issues for sanitation and of course there was no rubbish collection, instead simply piling up until the district could get it collected. This meant an infestation of vermin throughout the park’s surrounds.

The community as a whole were given less support than they could have been. After all, this is not a group of people that wanted to come to Bogotá. They were forced out of their homelands and given little viable other options than migrate to the big city.

Once there, they found themselves largely locked out of the city’s support systems. Access to the internet is limited for many in the camp, with electricity, too, largely absent. This makes it hard to get in touch with officials via their websites, chatbots and email addresses – critical for accessing a now largely digitised system.While there is limited support for the adults, children are a legal responsibility of local government in Colombia. The district services were run off their feet – the cost of medical interventions and educational support alone was around COP$18bn. This was a strain on a city already creaking at the seams in terms of providing for its citizens.