Leading Latin American human rights campaign group WOLA takes a look at some of the challenges in the year ahead.

Peace

The Duque administration won the presidential elections by promising to rip the peace accords to shreds. Its entire campaign platform was based on a promise that it would address the fears of the Colombian elite. Duque played on the right’s extreme hatred of the FARC and the Venezuelan government. In addition, Duque was Uribe’s chosen candidate and so the expectation was that he would revert to Uribista policies and/or be a puppet of the more radical members of the Centro Democrático Party.

Once in power, Duque found himself in an odd place. First, that the international community fully expects Colombia to advance and implement peace. If he does not do so, it could have serious implications in terms of foreign aid and international prestige. Second, that the infrastructure for peace was further along than his team anticipated.

The hope is that the Duque administration does not abandon the peace process nor spend months trying to reform commitments that were already agreed to. It should implement peace in an integral fashion and not pick and choose parts of the accord to follow.

For example, the agreements between the government and coca farmers included promises his government could not backtrack on. One of the biggest challenges Colombia faces is that while those who advocated a ‘No’ in the plebiscite campaign have reached the presidency and power in the Colombian Congress, this view of peace is not what the majority of rural, poor, Afro-Colombian, indigenous, victims and people living on the periphery of Colombian society desire. The government, therefore, cannot completely change course in the country – yet it needs to appease its backers.

As a result, we see a lack of clarity where it may appear to advance in rhetoric but not with the resources and political backing required. Compounding this, we hear different messages from members of the ‘No’ camp – some of which contradict Duque. The latter makes Duque appear weak or as if he does not fully control his administration’s agenda.

The hope is that the Duque administration does not abandon the peace process nor spend months trying to reform commitments that were already agreed to. It should implement peace in an integral fashion and not pick and choose parts of the accord to follow. If it does not want new dissident groups or increased membership of former FARC in criminal groups then it needs to meet its reintegration commitments to former combatants.

Further, the peace accord is not only for the FARC. It is an accord for all Colombian society including victims, women and marginalised populations. Of most importance, the hope is that the ethnic chapter of the accord is fully implemented as it could serve as a positive example for other peace processes around the world.

The JEP

The JEP is advancing in terms of the development of its institutions and its work. However, it is likely the JEP will face obstacles at every step that it takes – especially from the congress and certain media sources. The unfortunate false narrative that the FARC are ‘getting away with little punishment’ and that the having military participate in this process somehow diminishes their status as “heroes” has done great damage to the transitional justice system. This is a great disservice to the victims of the conflict.

By creating obstacles to truth telling from all sides of the conflict, the possibility of repeating violence increases. While not perfect, the transitional justice system set-up includes a very sophisticated set of institutions that could take a big step in advancing Colombia towards legality and reckoning with its past. Aside from the political obstacles the JEP will continue to face, given the sheer number of cases that occurred in over 50 years of conflict, it has the unenviable task of having to prioritise cases that will have the most effect in the country. As such, whichever cases it chooses will make others unhappy. That said, if the JEP accomplishes even 50% of what it’s tasked to do, this will greatly advance peace and human rights in the country.

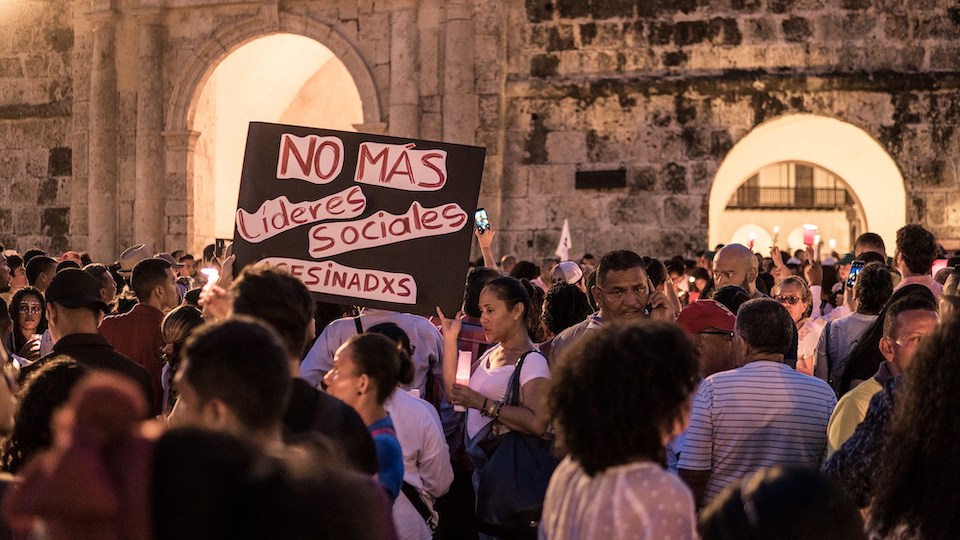

Social activist murders

The rate of killings is unlikely to fall. At the time of writing we’ve had nine more social leaders killed already this year. While the Duque administration has announced that it has a timely action plan for addressing this problem that includes increasing inter-institutional coordination, focusing more in the territories and destigmatising social leaders and their work, these efforts alone are not likely to work.

The reason that persons continue to kill social leaders is simple. They know they can get away with it as there is zero signal from authorities that this is not permitted. While the justice system has taken some action including increased investigations and coming up with better ways to systematise the cases, it has yet to make a real dent in showing that this is not ok.

Second, the persons and interests behind such killings remain in the shadows. A real concerted effort at justice to prevent further killings would involve putting the intellectual authors behind bars. Also it would include addressing corruption and collusion with members of the police and armed forces which leads to them looking the other way when these attacks take place.

Complicity from the private sector and civil authorities in these cases must also be brought to light. None of these killings take place in a vacuum nor are they isolated or arbitrary incidents. Many of them are basically ‘announced’ for months and at times years prior to their taking place.

Related: shock, sadness and fear initial reactions to Bogotá car bomb

The protection system run by the National Protection Unit needs to be revamped. First, corruption within this Unit needs to be addressed. Second, it should not be allowed to subcontract its services because this is where it loses a lot of money. Third, it needs to be streamlined. On paper, having multiple institutions and steps towards getting protection measures seems thorough and good. In practice, this is a nightmare. Not only does it make the process inefficient and costly but it leaves the recipients of such measures exposed and vulnerable for far too long.

Fourth, the protection system is not properly set up to cover rural leaders or urban leaders when they must travel outside of cities. The actual physical measures like a panic button, a bulletproof vest, bodyguards, etc can actually increase the persons’ risk or make them more of a target. The measures are not designed with the input of the recipient so on many levels they do not always work.

When it comes to Afro-Colombian and indigenous persons and other collective groups, there is no regard for those groups’ wishes and proposals for how they can best be protected. The ethnic chapter of the peace accord includes mention of measures like indigenous guards which these groups point to as the most effective method of protection for their leaders in rural, remote and hard to reach areas where the state is not fully present.

Additional challenges

- Effectively stopping the growth of coca cultivation and illegal economies such as drugs and resource extraction (such as gold).

- Handling the complex scenarios it faces with multiple armed groups, all illegal and all with different modus operandi.

- Corruption.

- A further increase in the mass inflow of Venezuelan migrants and refugees in need of humanitarian assistance, shelter, employment and the strain this is putting on its institutions and local communities.

Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli is the leading Colombia human rights advocate at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). She is an expert on peace and illegal armed groups, internally displaced persons, human rights and ethnic minority rights.