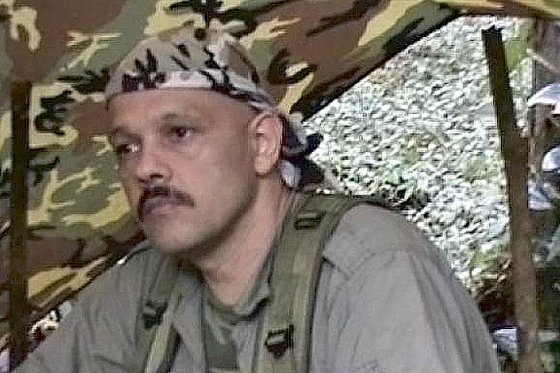

Iván Marquez (right) is the next FARC leader under investigation by US law officials after Jesús Santrich (left) has already been arrested. Photo: Santrichlibre.org

Possible extradition of FARC leaders Iván Marquez and Jesús Santrich puts extra strain on peace implementation.

“We’re drifting towards the abyss of war. They’re tearing apart peace.” Those were the alarming words of presidential candidate Humberto de la Calle in view of recent events that have put the peace process on edge yet again.

De la Calle, who was also chief negotiator and one of the key architects of the peace deal, made his statement following headlines that another FARC leader, Iván Márquez, was being investigated by US law officials. On April 9, a prominent member of the newly founded FARC political party, Jesús Santrich, was arrested on charges of conspiring to export 10 tons of cocaine. The ex-rebel, who has since gone on hunger strike, had to be transferred to hospital and now awaits probable extradition to the US.

The FARC insists that the incidents are part of an orchestrated plan to sabotage the peace process. While De la Calle has taken a more moderate stance, he underlined the importance of trying former FARC rebels in Colombia. “Extradition is not convenient. The Colombian people have a right to evaluate and know about the accusations in detail,” he explained.

The experience is not new to the country’s transitional justice processes. Massive extraditions of paramilitary commanders during Álvaro Uribe’s presidency were fiercely criticised by human rights advocates. They contended that the absence of the offender undercuts victims’ access to truth and justice.

Problems with implementation

This is just one of many serious hits the peace process has had to take in the past few months. Recently, a scandal emerged when the ambassadors of donor countries Norway, Sweden and Switzerland expressed concerns over the mismanagement of a $200-million fund set up to implement peace programmes in conflict-ridden areas. The government has fired the person in charge of the post-conflict fund, but there is still no clarity as to why the money has not been put to use.

Related: ELN peace talks on a knife edge

To compound things, the implementation of the peace deal has been slow and fruitless in many ways. Farmers across the country have not been given full access to productive land, and many are still forced to resort to coca production. Police have acted violently against coca farmers who oppose forced eradication, and those participating in voluntary substitution programs are frequently targeted by FARC dissidents and ELN fighters.

Reintegration of former FARC combatants is lagging, and security guarantees for demobilised rebels have been highly ineffective. Since the signing of the peace agreement in November 2016, 48 ex-combatants of the FARC have been murdered and six have been forcibly displaced. Jean Arnault, chief of the UN Monitoring Mission in Colombia, emphasised the need to expedite the reintegration process before the end of President Juan Manuel Santos’s mandate. “Weaknesses in this effort can only increase the risk of the drift of some ex-combatants to criminal groups,” Arnault said in a statement before the UN Security Council.

The rising tide of violence in rural parts of the country has also endangered the lives of human rights defenders. The Ombudsman Office registered 282 killings of social leaders between January 2016 and February 2018, and many non-governmental reports point to an even higher number.

Modifications

In addition, proponents of the peace deal are worried about many of the modifications congress has made to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, a tribunal in charge of trying those responsible for human rights violations. Under the changed version, third parties involved in the conflict (such as businesses that financed illegal armed groups) are no longer obligated to appear before the transitional justice court.

Modifications like this might be taken a step further should an anti-peace agreement candidate win the upcoming presidential elections. Frontrunner Iván Duque, protégé of former president and right-wing hardliner Uribe, has long vowed to reverse the peace agreement. In his remarks, De la Calle accused both Duque and Uribe for “weaving a fabric of hatred and lies”.

“I invite Iván Duque to come forward and face each and every single victim and tell them how exactly it is he plans to tear apart the peace deal,” he said.

The peace process has suffered and survived many blows since its signing in 2016. There is still reason to believe that it will endure this crisis as well, but backers of the peace deal must come together and defend it collectively. When peace was at the brink of collapse following the plebiscite, thousands across the country mobilised and demanded that the agreement be implemented – and it worked. Peace proponents will have to regain momentum across party lines if they want to effectively face the new challenges and stand up to a government potentially opposed to the existing agreement.