The plebiscite: a clever negotiating strategy or a unnecessarily risky inclusion of the voting public.

Many have asked why the peace deal needed to be put to a public vote. Conflict resolution specialist Thomas Stevenson argues that, while there were some tactical negotiating benefits to the plebiscite, it also entailed a lot of avoidable risk.

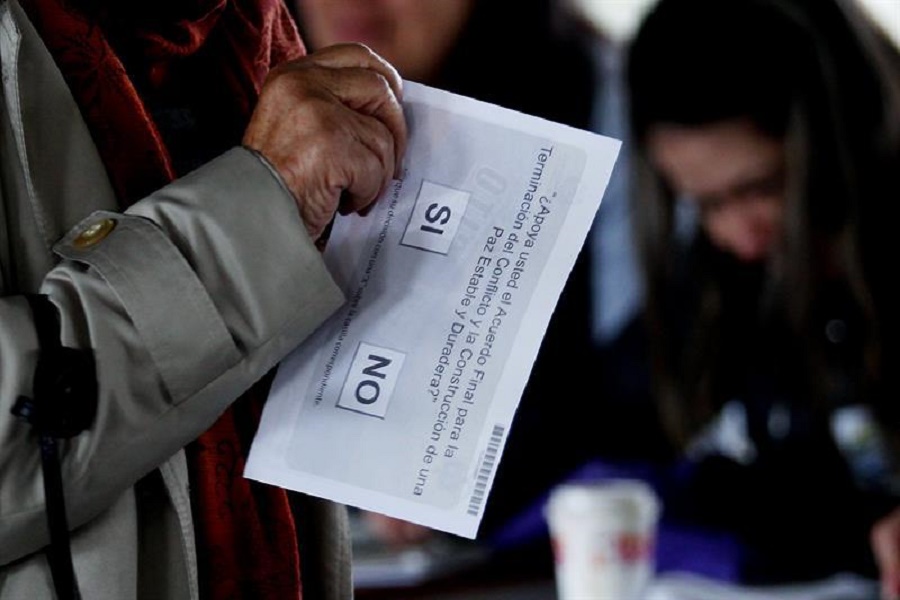

Readers will need no reminding of the events of October 2. Leading up to the peace deal plebiscite, each side had staked out its position and dug in: supporters were prepared to make concessions to end a historically-lengthy war; opponents argued the terms of the agreement were too lenient.

With polls auguring a comfortable win for the ‘Yes’ camp right up until voting day, it is hard not to think ‘Yes’ supporters let complacency get the best of them. Whatever the explanation, the referendum and its startling result are now history. There will be no end of debate as to whether a ‘No’ vote was the best thing for Colombia. Setting such questions aside, however, one cannot help but wonder how on earth the validity of a government-FARC peace deal, almost four years in the making, ever came down to a vote in the first place.

Santos himself said publicly before the referendum that there was no Plan B in place should the ‘No’ side prevail. What at first blush seemed like a discomfiting lack of preparation may in fact have been a calculated move: some have speculated that, by announcing he would leave the fate of the deal and the foreseeable future in the hands of a public sceptical of the entire process, Santos gave government negotiators in Havana a powerful weapon to secure concessions from FARC negotiators sincerely hoping not to return to the jungle. For the same reason, the government may not have done everything in its power to influence public opinion in the months leading up to the referendum – overwhelming public support could have led FARC negotiators to think they had surrendered too much and backtrack. But what good is a favourable deal if it’s DOA (dead on arrival)?

Why hold the referendum?

So why did he do it? Does gamesmanship justify imperilling years of dogged negotiation? Make no mistake: Santos was under no obligation to hold a referendum. Rather than place his fate in the hands of his detractors, he could have used his political capital to hammer the deal home. Negotiation literature, however, suggests at least one theoretically sound explanation for the president’s choice.

Make no mistake: Santos was under no obligation to hold a referendum. Rather than place his fate in the hands of his detractors, he could have used his political capital to hammer the deal home

Research has consistently shown that deals are more durable when they enjoy buy-in from all stakeholders. Santos probably was not naive enough to think he would win over die-hards in Senator Uribe’s ‘No’ camp, but, by including and outvoting them, he may have planned on lending the deal the sheen of public acceptance.

Even as negotiation theory supports Santos’s choice to include society as a whole, it skewers his chosen means of doing so: a last-minute, all-or-nothing vote is not the only way to show you have society-wide buy-in.

In works like Breaking the Impasse, multi-party negotiation specialists Lawrence Susskind and Jeffrey Cruikshank have written at length about how those staging complicated talks can ensure that all stakeholders feel a final agreement addresses their interests without the need for a referendum. In a nutshell, the need for a vote is obviated by assembling negotiating teams according to the following principles:

1) All relevant groups have authorised representatives to make decisions on their behalf.

2) These representatives have made the effort of consulting with their constituents throughout talks.

3) No groups seeking to participate have been left out.

If these three criteria are met, the parties, having entrusted negotiators to represent them, lose the right to object to any deal these representatives approve.

To some extent, the Havana negotiations reflected this wisdom. In 2012, the United Nations and Universidad Nacional staged a series of forums throughout the country to determine who should participate in the peace talks. Groups ranging from women to campesinos received permission to send delegations of 30-40 people to Cuba. In many cases, representatives arrived in Cuba bringing years – if not decades – of experience of representing their respective constituencies. Campesinos, for example, sent the heads of farmers’ guilds and congressmen with track records of advocating in favour of agrarian reform. The same relationships that had allowed these people to act as public servants enabled them to easily confer with constituents as the details of a peace deal emerged. On criteria one and two then, Santos’s administration did a beautiful job.

It was on Susskind and Cruikshank’s third criteria that the government dropped the ball. Afro-Colombian and indigenous minorities spent nearly four years – or nearly the entire length of the negotiations – demanding to have a say. Fearing the special rights afforded these groups under Colombian law would slow talks to a crawl, the government held out until August 2016 – barely a month before the Cartagena deal signing ceremony.

Whereas the ‘Yes’ camp signalled its contentment with one option (the peace deal as hashed out in Havana), the lack of any Plan B invited ‘No’ voters to indulge their wildest ‘perfect deal’ fantasies

When Afro-Colombians and indigenous plaintiffs finally received permission to form a delegation, La Comisión Nacional Étnica de Paz, the issues these groups cared about (rural reform, illicit crops) had already been settled. In the end, chief government negotiator Humberto de la Calle accepted a meagre four-page submission from La Comisión that essentially guaranteed the deal would not supersede existing agreements between Afro-Colombians or indigenous communities and the government. By insisting from the start that every group seeking to participate in negotiations be allowed to do so, Santos could have earned the right to skip the referendum and still claim he had Colombia’s support.

‘No’ opened way to perfect fantasies

From a negotiation perspective, why was Santos’s failure to satisfy this third criterion such a mistake? In multi-party negotiations, representatives keep the lid on Pandora’s box by limiting the number of parties at the table. Santos would never have attempted a negotiation between all 47 million Colombians – not because there is no negotiating table large enough, but because doing so would instantly paralyse talks by the sheer diversity of opinions. Yet, perversely, this is what the plebiscite did. Whereas the ‘Yes’ camp signalled its contentment with one option (the peace deal as hashed out in Havana), the lack of any Plan B invited ‘No’ voters to indulge their wildest “perfect deal” fantasies. Some wanted to chip away at specific parts of the deal such as monthly government payments and guaranteed congressional seats for the guerrillas. Others yearned for the return of Uribe’s patented “law and order” brand of governance. Still others understood on some level that the deal enjoyed LBGTI support, and marked ‘No’ thinking they were protecting the institution of marriage.

Whatever form it takes, the ultimate outcome will not satisfy each of these demands. It may not satisfy any of them. But it doesn’t matter. After four years, Santos’s biggest blunder to date untethered Colombians from their representatives and, on October 2, created a ragtag coalition of dreamers, malcontents, and solipsists. In the open-ended ‘No’, voters saw what they wanted to see. The lid is off the box.

Thomas Stevenson is a conflict resolution specialist who has worked with the United Nations, NGOs and policy think tanks in conflict/post-conflict zones including Myanmar, Cambodia, and Colombia. He is the founder of Colombia-based firm Strata Consulting SAS and lecturer in negotiation at Universidad de Los Andes.