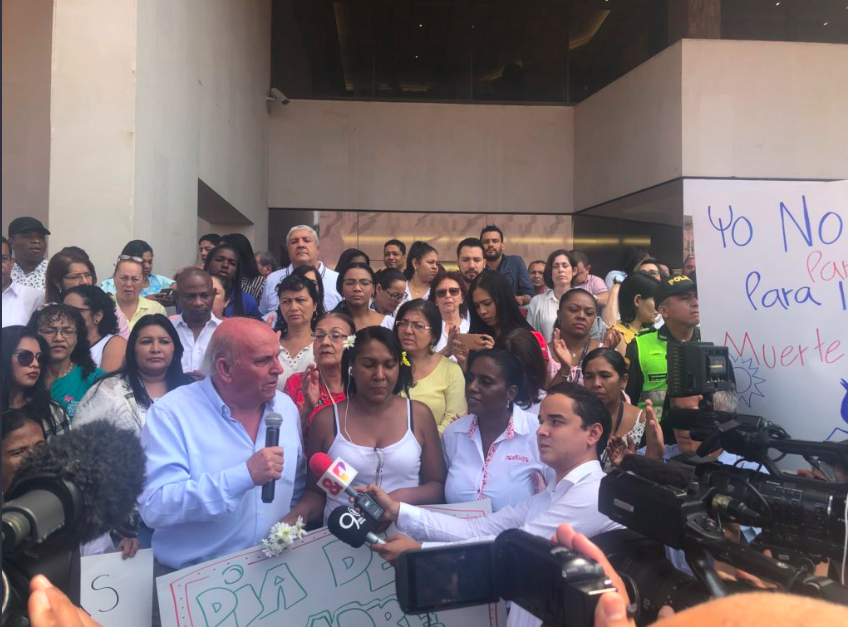

Image courtesy of @GermanVargasLle

Germán Vargas Lleras has always been there. He was there to see his grandfather rule Colombia under the banner of conservatism and run a program of national transformation. He was there when the liberals coalesced around Luis Carlos Galán. He was there in Soacha when Galán was then cruelly gunned down in 1989. Then, at the turn of the millenium, he was there to support Álvaro Uribe during his tenure as president and then, as vice president, he watched as Santos made peace with the FARC. He now runs for President as leader of Cambio Radical and has positioned himself as a hard man with a hard line on crime.

The life of a career politician may not be principled but it is based around one important rule: do what is necessary to persevere. Vargas Lleras has persevered through ideological changes and formative experiences. Which is one reason why in this race, despite registering single digits in the polls, no one has ruled him out of contention just yet.

Trained as a lawyer, Vargas Lleras persevered through two bomb attacks, one which left him with only three fingers on his left hand. Having survived both of them added to Vargas Lleras’ ‘tough guy’ image which he has used to his advantage when speaking of national security. During the debates this year, Vargas Lleras exuded experience and his wry wit won him admirers, even within enemy territory.

Famous for his short temper, journalists have often been at the rough end of his no-nonsense irascible approach, typified most recently in an interview this week when a radio host asked him hard-hitting questions like “when was the last time you cried” and “when was the last time you felt happiness?”

Vargas Lleras’ dry response was “Que preguntas tan chimbas,”; a sarcastic response that combined the belittling of a journalist with the common vulgarity of the word chimba (which means ‘vagina’ in Colombian Spanish).

It’s too early to underestimate Vargas Lleras’ popularity in Colombia, even if he is backed by a deeply unpopular president. An article in Semana argued that “the former vice president holds on to the votes that the polls find difficult to measure.” This concept, referred to as ‘the silent majority’ in English, is another reason why no one has ruled out a Vargas Lleras presidency.

During the campaign, Vargas Lleras made the argument that his experience should indicate what he would do as president. After Santos won the 2014 elections, he appointed Vargas Lleras as his Minister of Interior and then Minister of Housing. After becoming Santos’ Vice President, further ambitious reforms on infrastructure came about. He hopes to build on his time as Vice President by pledging build a further 1.2 million homes under an ambitious housing plan.

Job creation would be a priority of a Vargas Lleras presidency and, to this end, he also hopes to boost the tourism industry claiming that 800,000 jobs across four years will be added to this sector. He also plans to raise the number of specialists within the healthcare system and his policies include the increase of hospital investments and the improvement of the public-private partnerships in constructing healthcare facilities.

But the centrepiece of his proposals is on the issue of security and an increased hardening on crime. For example, he is for lowering the age of criminal responsibility from 14 to 12 years and stricter sentencing policies for juveniles between 14 and 18 that have committed serious crimes. His justice reforms would involve making the sentencing process quicker and plans to do away with INPEC, an inefficient intermediary in his books. On a related note, he wishes to maintain the prohibition of firearms and extend the prohibition to knives as well.

On the environmental front, Vargas Lleras is strongly against illegal mining and wishes to transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy in his hope to continue compliance with the Paris Agreement.

And though he has also promised to maintain the peace accord, his public stance against the historic agreement, particularly on impunity for former FARC fighters, has caused concern among those who wish to continue its full implementation. He has stated that he will not support any similar agreement with the ELN. On the related issue of drug use and trafficking, Vargas Lleras wants to criminalise the consumption of marijuana and cocaine and get stricter on trafficking.

His more hardened views also sometimes relate to social and environmental issues. In 2002 he was one of the champions of paternal rights of gay couples. This year, he has spoken out forcefully against gay marriage and is also against adoption of children by gay couples.

In addition to these conservative proposals, there are other pledges that suggest he may not have entirely shed his liberal roots. For example, he is for an increase on maternity leave, including workers without contracts, and he is also an advocate of affirmative action in relation to minority and indigenous members.

In his long career in politics, multiple allegations have been made against Vargas Lleras of corruption. Columnist León Valencia said of the Cambio Radical leader that “the most difficult thing for Germán Vargas Lleras won’t be to commit to peace and a post-conflict nation, his biggest challenge will be to defy corruption and crony capitalism…His party, Cambio Radical, has endorsed a legion of corrupt politicians, some of them gangsters and criminals that are in deep judicial troubles of their own.”

Voters tiring of corrupt politicians will take a Vargas Lleras victory this Sunday as an electoral shock that will raise suspicions not only of the accuracy of Colombian pollsters but the possibility of electoral fraud. And if no such shock materialises, one thing is for sure; Vargas Lleras was and is always going to be there. This cachaco ain’t going nowhere.