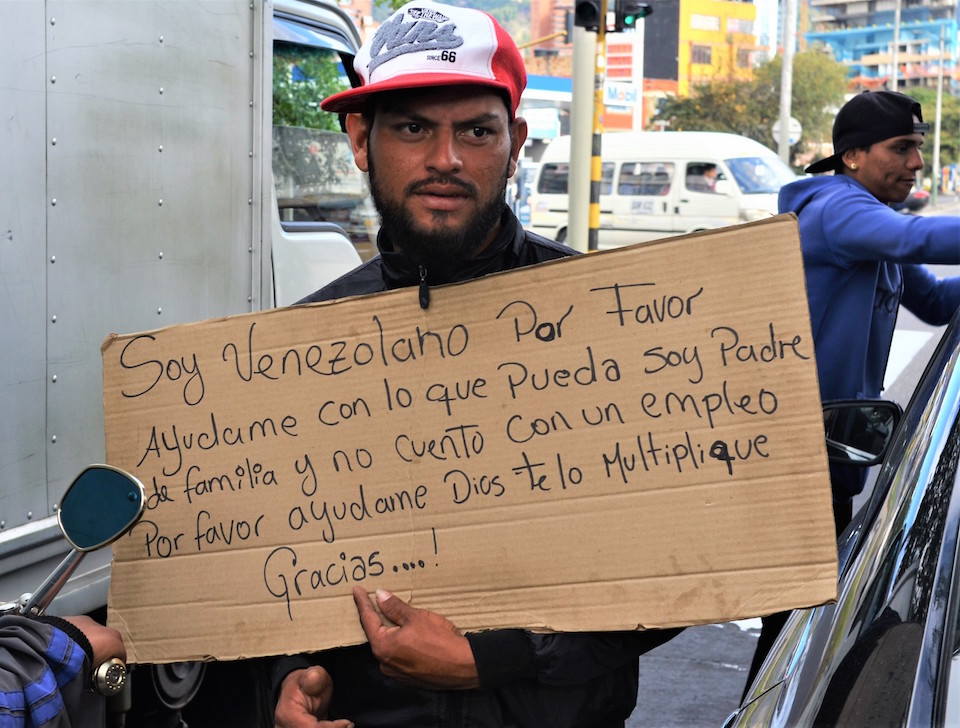

Jaifer, a mechanic from Carabobo, begs on a Bogotá street. “I have no choice since I can’t find work and there’s no food back in Venezuela.” His wife and two children rely on the coins he collects each day.

With at least a million Venezuelans in Colombia, we look at what is driving them out of their homes and what is waiting for them.

Venezuela was once a wealthy nation boasting the world’s largest known oil reserves. Now it’s a failed state with millions of people fleeing economic collapse. The UN called has called the exodus of people “a crisis without precedent in the region”, comparing it to the dramatic movement seen in the Mediterranean in 2015.

Extreme hyperinflation of currency, deterioration of the healthcare system, power cuts, and food shortages among other issues have driven people out of the country.

People have been leaving the country in droves – hitchhiking and traveling by bus or by foot to survive. According to the UN, there are now 2.3 million Venezuelans living abroad – more than half of whom have left since 2015. The Universidad Central de Venezuela has put the number as high as four million.

Migration officials say that there are about one million migrants in Colombia, with almost 25% of them stopping in Bogotá. When we first went to the bus terminal in Salitre at the start of September there were about 100 people camping out, just four days later numbers had swelled to 250.

Read our full coverage of the Venezuelan migrant crisisThis is how you can help: Several organisations can do something with your help.Interviews with Venezuelans #1: ‘We left because there was no food.’Interviews with Venezuelans #2: ‘I had to leave because I denounced the corruption.’Going Local, Voting with their feet: Columnist worries that goodwill has an expiry date.Compassion and condemnation: The struggle for acceptance in a crowded capital.Crisis is just beginning: NGOs raise alarm over situation for fleeing Venezuelans. |

The country is suffering from spiralling hyperinflation that the government has been unable to stop. The Financial Times said inflation reached 83,000 percent last month (compared to 2.9 percent in the US) and the IMF say it is heading for one million percent by the end of this year.

Venezuela’s dependence on oil has been a significant factor in the country’s collapse. Amnesty point out that a whopping 96 percent of the government’s revenue came from oil exports. When the global oil prices dropped, it sparked “a grave and complex economic crisis.” The human rights campaign group said, “By 2017 poverty had increased to 87% and extreme poverty to 61.2%.”

With drastic drops in both food imports and domestic production, prices have soared and many of the 32 million Venezuelans face hunger and starvation. Several media reports say that on average, adults have lost 11 kgs in weight in the last year and many children are malnourished.

Venezuela’s leaders are denying the crisis. The current government – led by Hugo Chavez’ handpicked successor Nicolás Maduro – told a press conference at the start of September that the exodus is a ‘normal migration pattern.’ They insist that news reporting of the migrants and suffering in Venezuela itself is propaganda to justify foreign intervention in the country.

The economic collapse and ensuing humanitarian crisis also mark a milestone in relations with neighbouring Colombia which has often been politically diametrically opposed to Venezuela. All of this results in mutual mudslinging with claims and counter-accusations of border incursions, harbouring armed groups and state-sponsored subterfuge.

The Caracas regime has been often portrayed as a mentor to Colombia’s left-wing guerrillas who were known to take refuge over the border.

But international politics barely matter to the ever-increasing number of new arrivals. They need access health, education and employment. For many, a lack of passports or identification papers forces them out of the formal economy and into the less stable informal economy. And according to WOLA and several other NGOs, they are falling prey to recruitment by armed groups, especially in conflict-ridden border zones.

Additional reporting: Steve Hide