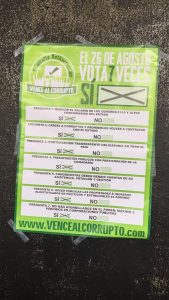

Photo courtesy of Facebook Grupo Alternativo Consulta Anticorrupción

The voting of the long-awaited Consulta Anticorrupción will be held tomorrow and promoters and critics are sharpening their best arguments to persuade the public. Promoters are roving around the country talking directly to voters, while the critics are carrying out an opposition campaign through social and news media.

But, who is against the Consulta and why? This is a difficult question to answer considering that the proposal passed unanimously through the upper house of Congress; all the parties and presidential candidates demonstrate their support in public debates, including the elected president Iván Duque and Centro Democrático (majority party) leader Álvaro Uribe.

There’s no consensus within the group of public figures who are against the consulta* and only a few have decided to argue publicly against the 7 points included in the voting.

The call for abstention

Before Aug. 7, the date of the presidential handover, many believed that the new government and their party were supporting the initiative, or at the very least weren’t banning it. It all changed when a Noticias Uno journalist infiltrated and recorded the Centro Democrático meeting held after the inauguration, where it was known that Álvaro Uribe didn’t want to support the consulta. The following day, Senator Uribe stated during a congress session that he preferred to support a law proposition made by the president which included many of the points of the consulta, labelling the proposal as ‘more complete’ compared with the ones in the consulta.

Prefiero apoyar la legislación propuesta por el presidente Iván Duque, que es mucho más completa, para enfrentar la corrupción pic.twitter.com/fB7LS7LWdT

— Álvaro Uribe Vélez (@AlvaroUribeVel) August 8, 2018

Last week, Centro Democrático congressmen and president of the senate Ernesto Macías, stated that he was not supporting the Consulta due its high costs (300 billion pesos) and because he’s against lowering the wages of congressmen (first point of the initiative).

Following this, some conservative public figures, including the Centro Democrático leaders, promoted the hashtag #SinGastar300MilMillones (without spending 300 billion), criticizing the high costs of the voting process and supporting the initiative of the president.

El combate a la corrupción no requiere consulta#SinGastar300MilMillonespic.twitter.com/BobcJDAGyW

— Paola Holguín (@PaolaHolguin) August 19, 2018

Besides this, President Duque has repeatedly pledged his support to the consulta, which confirms the statement of senator Paloma Valencia: “one thing is the government, another thing is his party”.

Whereas the initiative reaches the 12 million voters or not, president Duque and his supporters in Congress have promised to run their own anti-corruption law proposal. However, the main points of the current consulta were rejected eight times as a law by the Senate between 2014 and 2017, a fact that explains why the Partido Verde (Green Party) decided to change it into a public initiative that resulted in the upcoming vote.

The call to vote against

Many journalists and scholars have argued against some points of the initiative, because there are already laws which contemplate the sanctions proposed or they consider them ineffective to deal with corruption. Some of them manifested their intention to vote some points Yes and others No.

El Tiempo columnist Maria Isabel Rueda argues that “98% of the proposals already exist in our laws”. For instance, she explains, the mandate to declare income, wealth and inheritance statements for public servants before and after their service period (point 6), is already in article 13 of law 190 of 1995.

The unilateral ending of contracts with people found guilty of corruption (point 2) also exists in law 80 of 1993, as well as the prohibition of house arrest of people found guilty of corruption in law 1474 of 2011.

Gustavo Álvarez Gardeazábal, a renowned Colombian journalist, labeled the questions posed by the vote as populist, saying that those mandates already exist even if they aren’t being applied.

Meanwhile academics like Jhon Fernando Restrepo, constitutionalist and university professor, told us that point 1 (reducing the salaries of the Congress members) and 2 are against the Social Rule of Law promoted in the Colombian constitution, because salaries cannot be decided by the popular vote and no one can suffer perpetual punishment under the constitution.

To reach the 12 million voters needed to pass the civil initiative, promoters of the Consulta will also have to fight against apathy and misinformation; some fake news has spread by way of social media, saying that promoters will get $5,000 pesos for each vote or that the minimum wage would also be reduced if the consulta gets enough votes.

Many believe that reaching such a high threshold of votes needed is impossible with the under-the-table opposition of the Centro Democrático and the conservative regional elites, who could persuade many of Iván Duque’s 10 million voters to abstain from voting. Promoters will have to appeal beyond ideologies to persuade those Colombians who perceive the initiative as a platform for the Green Party leaders to gain more political control.

*Note: a consulta means a query, which is different from a plebiscite or a referendum. It’s a civil initiative (the other two are proposed by the government) and creates a mandate that can’t be modified, either by the president or congress.

This article originally appeared in Colombia Focus.