Mike Mackenna presents the case against the three principal suspects for the recent TransMilenio COP$200 fare increase, bringing the total cost to COP$2,000 per ticket

Mike Mackenna presents the case against the three principal suspects for the recent TransMilenio COP$200 fare increase, bringing the total cost to COP$2,000 per ticket

The 2011-2015 City Council |

|

| The case against them:

• Former mayor Gustavo Petro proposed implementing congestion charges in Bogotá three times, partly in order to raise the money to make fare hikes unnecessary. The council rejected the proposal every time. • The council gave three reasons for their repeated rejections: one, it was unfair to punish people for using cars when public transport in Bogotá is so poor, two, the roads are in such disrepair that the government doesn’t have the “legitimacy to establish these charges”, and finally, the city’s secretary of mobility failed to have the charges fully evaluated by the national ministry of transport. |

Case analysis:

• The council has a point about the inadequacy of public transport, although encouraging people to keep using cars until public transport is improved hardly seems to be the solution. • The council’s road repair argument put Petro in a Catch-22 situation: he wanted to use the congestion charges partly to fund repairs, but he couldn’t implement charges until there were more repairs. • Their argument that the ministry of transport did not evaluate the charges seems dubious, since the minister herself encouraged Petro to push for the charges in January 2015. |

|

Related – Colectivos getting the SITP blues Former mayor Petro (2011-15) |

|

| The case against them:

• In 2012, Petro lowered TransMilenio fares by COP$300 during non-peak hours, without doing any studies about the economic impact. The city had to pay COP$1.52 billion (about USD$500 million) to the fare stabilisation and contingency fund as compensation for the price reduction. Petro reversed the decree in August 2015. • City comptroller and anti-Petrista favourite Diego Ardila warned the mayor three times about the need to reverse the decree. • According to Semana, following the city council’s rejection of the mayor’s three requests for congestion charges, a draft proposal was prepared to raise the TransMilenio fares. However, Petro refused to sign it. Petro’s previous TransMilenio manager, Sergio Paris, told El Tiempo, “Either you raise the TransMilenio fare or you subsidize it.” • Petro’s old nemesis, Procurador Alejandro Ordoñez, is preparing an investigation against the former mayor for not raising the fares. |

Case analysis:

• It is difficult to defend Petro’s decision to lower the fares without doing the appropriate studies. Ricardo Bonilla, Petro’s secretary of the treasury at the time, thought the lowered fares would bring more passengers. Petro’s TransMilenio manager Fernando Rey, called it a decision based on a political commitment. • Petro’s refusal to raise fares in spite of the recommendations he received to do so could be seen in two ways: as a principled stance in favour of public-transport users, or as a failure to fulfil his responsibility to take care of the city’s finances, possibly motivated by a desire to protect his 2018 presidential ambitions. • Petro might be guilty of negligence in not raising the fares, but any Ordoñez-led investigation of Petro is questionable to say the least, after the Interamerican court of Human Rights ruled that Ordoñez’s attempt to impeach Petro in 2013 was a threat to the former mayor’s political rights. |

|

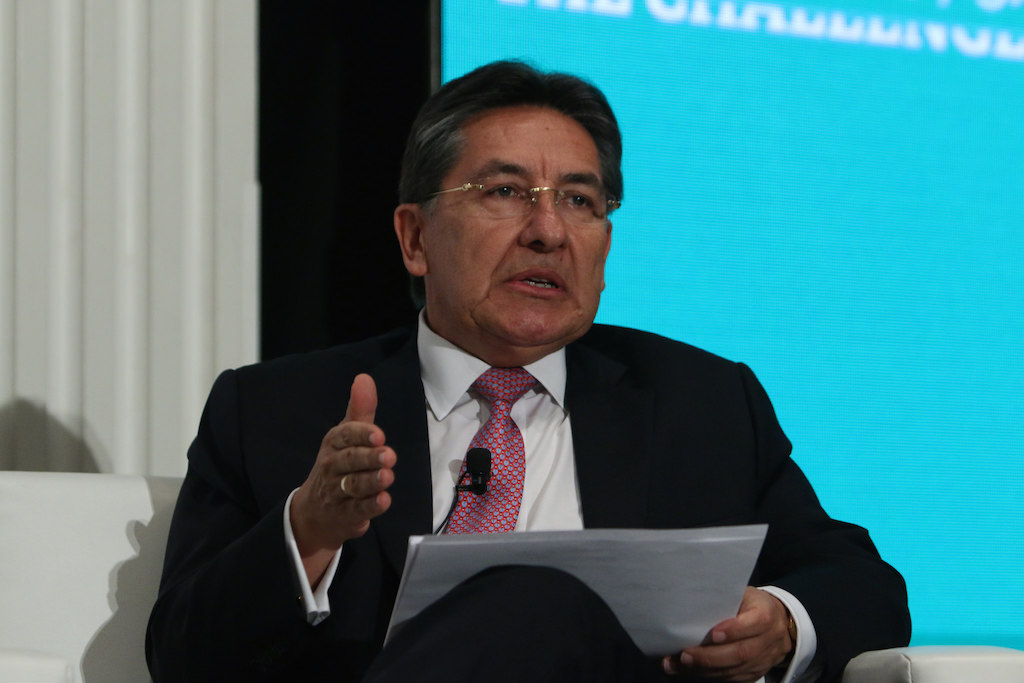

Related – Moving forward Mayor Enrique Peñalosa |

|

| The case against them:

• Peñalosa increased the fares because he has ruled out the alternative of using congestion charges to raise money for the TransMilenio. Even though Peñalosa will be taking another shot at getting congestion charges passed by the city council, the mayor is not planning to use the congestion charges to subsidize TransMilenio fares, opting instead to build new roads. |

Case analysis:

• No one doubts that the TransMilenio needs more money, but it’s far from clear that the additional funds should come from the passengers, considering that low-income Bogotanos are already spending 20% of their income on public transport. • Peñalosa’s decision to use the congestion charges to build roads instead of subsidise TransMilenio fares could also be seen in two ways: as the only politically possible way to get the council to approve a badly needed congestion charge, or as another example of his supposed tendency to neglect the most vulnerable Bogotanos. |